Dhonowlgos

| Dhonowlgos Hineskeyos Dhonowlgos | |

| Flag | Coat of arms |

|---|---|

|

|

| Motto: Hungwios Dlrocha Hortih - Under the light of Dlrocha | |

| Anthem: | |

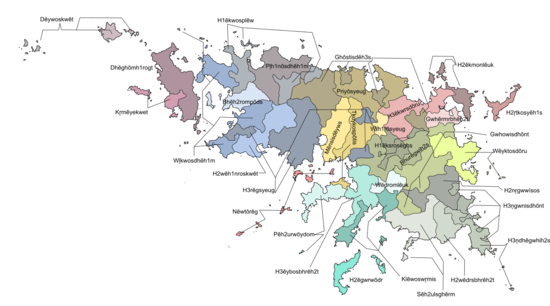

| Locator map | |

| |

| Capital city | Dhowkros |

| Largest city | Dhowkros |

| Official language | Wolgos language |

| Other languages | |

| Ethnic group | |

| Religion | Dlroch'velder |

| Demonym(s) | Wolgos, Eokoesr |

| Government | |

| Government Type | Theocracy |

| Vlroika | H3regwos H3regwusonos |

| thc | tbc |

| Legislature | Whorleda |

| Establishment | |

| tbc | 3010 CE |

| Area | |

| Total | tbc km2 |

| Water % | 5.6% |

| Population | |

| Total | 23,821,410 |

| Density | tbc/km2 |

| Economy | |

| Economy type | Feudal |

| GDP (total) | Ꞡ tbc |

| GDP per capita | Ꞡ tbc |

| Currency | Vrock (tbc) |

| Inequality index | tbc |

| Development index | tbc |

| Other information | |

| Time zone | tbc |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | none |

| Internet code | none |

Dhonowlgos was a theocratic nation located on the Dnkluwos Islands in the northern region of Anaria. It stood as the center of Wolgos existence for countless millennia, remaining a secluded and mysterious entity, known to very few in the world of Gotha until the advent of the industrial era. The nation fiercely resisted any foreign intrusion throughout its history.

However, everything changed when the Dhonowlgos opened up to the world and joined the Pan-Anarian War. This decision marked a turning point in its fate. The war resulted in a conflict with Helreich and other Anarian nations, ultimately leading to the nation's downfall and destruction. As a consequence, the Wolgos were exiled to their sole colony on Altaia, where they had to rebuild their lives after the loss of their once-great theocratic nation.

Here the essence of the nation as it existed at its height before its downfall is presented.

Etymology

The etymology of "Dhonowlgos," the name of the Wolgos nation, reflects the intricate linguistic heritage of the Wolgos people, rooted deeply in their ancient language as it existed in the 3rd millennium. The name "Dhonowlgos" is composed of several elements that together convey a profound spiritual significance. The term dhono translates to "flow" or "run," indicating a continuous movement, while wlgos is derived from "the voice that comes," symbolizing a divine or sacred utterance. Therefore, "Dhonowlgos" can be more accurately translated as "the Continuity of the Sacred Voice," encapsulating the enduring and unbroken transmission of spiritual or divine communication throughout their society.

This name emphasizes the Wolgos' reverence for their mystics, who convey the word of Dlrocha, their god, through psychotic visions, delusions, and deliriums. The linguistic structure of "Dhonowlgos," though ancient, reveals a complex and nuanced understanding of language and meaning, reflecting the Wolgos' sophisticated approach to naming and their deep connection to their spiritual beliefs. These mystics, often seen as the vessels through which Dlrocha’s divine will and knowledge flow, were central to the societal and religious fabric of Dhonowlgos. Their visions and utterances, despite being rooted in mental disturbances, were revered as the sacred voice that guided and shaped the destiny of their people.

Thus, the name "Dhonowlgos" encapsulates the Wolgos' deep-seated belief in the mystical continuity of divine guidance, maintained through the sacred, albeit turbulent, voices of their holy visionaries. This sacred voice, carried through generations, was believed to ensure the nation's prosperity, cohesion, and spiritual alignment with Dlrocha’s will. The nation of Dhonowlgos, therefore, was not merely a political entity but a manifestation of divine continuity, a sacred realm where the flow of the divine voice perpetually guided and influenced its people.

History

Pre-history -16000 CE to -7300 CE

The Dnkluwos Islands have, for over twenty-three thousand years, been inhabited by various hominid species, enduring the merciless cycles of Gothan tyreal climatic oscillations. These cycles have drastically transformed the landscape, with the volcanically active islands transitioning from cold boreal forests and tundra during the coldest phases to warm temperate and dry climates in the south during the warmest periods. During the distal ice age, the Dnkluwos islands were unified into a single landmass, forming a large peninsula connected to neighboring Stoldavia by low-lying islets, brackish tidal marshes, and sand bars. The islands were cold, densely forested with ancient trees and conifers, transitioning to sparsely forested and barren mossy tundra in the north, with highlands covered by icecaps and glaciers that deeply etched the landscape.

Humans were the first to traverse the land bridge, forming Neolithic fishing and hunter-gatherer communities among the islets and marshes, slowly advancing into the more fertile Dnkluwos islands. These early settlers, ancestors of the Eokoesr, thrived by maintaining a delicate balance of hunting, foraging, and fishing in a bountiful yet unforgiving landscape. They crafted the first tools to grace the lands, including flint and bone knives, arrowheads, wooden spears, and woven bark baskets. The arrival of humans marked a significant era of adaptation and development as they carved out a niche in this diverse and challenging environment.

About two thousand years after humans arrived, as the climate cooled and competition increased in Anaria, the Wolgos were pushed from Anaria Major to Stoldavia and subsequently to Dnkluwos. The Wolgos, a distinct hominid lineage, had evolved in parallel with humans. Originally a hominid tribe struggling to survive, they became cannibalistic out of desperation, preying on more successful human tribes. This predation became their way of life, profoundly transforming them. The Wolgos adapted to become formidable predators of humans, evolving to be stronger and more physically imposing, but also requiring more calories, which led to the development of energy-conserving, stealthy stalking tactics. Their predation forged them into symbiotic partners in survival, altering the landscape with artful traps for both humans and animals.

The Wolgos shadowed the human settlers entering the islands, stalking and preying on tribes as they crossed the land bridge. Despite their formidable physique, the Wolgos were victims of their lifestyle, pushed out of Anaria by more adaptable and innovative humans. The few Wolgos who followed humans into Dnkluwos, numbering perhaps four hundred globally, lived with minimal tools or clothing, relying on roughly butchered pelts and primitive stone cutting tools. They depended on brute strength for hunting and butchering, with more developed tools found in their shelter caves often of human origin.

Human art from this era documents the arrival of the Wolgos, depicting them in cave paintings as limestone-white humanoid figures hunting humans. These paintings served as warnings or instructions on how to avoid or defend against the Wolgos. White female figures representing danger and surrounded by death suggest the Wolgos used honey pot traps, with women as seductive lures to entrap human hunter-gatherers. Myths of ghostly female wraiths or temptresses in Anarian and Stoldavian folklore may originate from this Wolgos tactic.

As the Wolgos adapted to their new environment in Dnkluwos, they continued to evolve both physically and culturally. Their society became increasingly specialized, with distinct roles for males and females, and a strong emphasis on stealth and predation. The harsh climate and limited resources necessitated a lifestyle of careful resource management and strategic planning. Over time, the Wolgos developed a complex social structure, with leaders emerging based on physical prowess and cunning.

In contrast, the Eokoesr human communities in Dnkluwos were evolving their own complex societies. They developed advanced fishing techniques, agriculture, and animal husbandry, gradually shifting from purely hunter-gatherer lifestyles to more settled forms of existence. Their social structures became more intricate, with tribal leaders and shamans playing central roles in their communities. The Eokoesr were innovative, creating new tools and methods to improve their chances of survival and prosperity.

Eokoesr Lordship Era -7300 CE to -4400 CE

- Main article: Stained Era

As the ice age gradually relinquished its grip on the world, Dnkluwos underwent a profound transformation. Changing ocean currents and a warming climate led to a rise in sea levels and the erosion of the land bridge, effectively isolating Dnkluwos and transforming it into an archipelago. The Wolgos, who had been extinguished elsewhere, witnessed a burgeoning human population as the islands experienced increasingly hospitable conditions. Despite these changes, the precarious path the Wolgos treaded would have likely led them to remain as primitive as when they first arrived, ultimately facing their decline and possible extinction.

A pivotal change occurred at the end of prehistory during the era of the Eokoesr “lordships.” This was a time when human tribes began to settle and form permanent villages, evolving into agriculturalists and pastoralists. These human communities grew more powerful but still feared the forests and highlands where the Wolgos had been driven. Evidence suggests that human tribes began to enter into territorial conflicts with each other, with raids becoming frequent as populations expanded.

In a remarkable turn of events, a human tribe sought out the Wolgos, their mysterious old foes from the deep forests. They sought them out of desperation or as a means to gain an edge over their human adversaries. The result was a pact that would fundamentally alter the course of history for the Wolgos, the Eokoesr, and the world. Archaeological evidence indicates that the Wolgos began working as mercenaries for human tribes, a practice that expanded across all Wolgos tribes. Their cave shelter sites show a dramatic rise in the use of tools and advancements in garments, pottery, and leather making, suggesting a clear transfer of human-made goods and skills to the Wolgos.

As centuries progressed, the Wolgos abandoned their caves and established new satellite settlements in defensible positions close to human communities. These settlements featured large thatched roundhouses with hearths and significant waste pits filled with animal and human bones. The Wolgos became integral parts of these human communities, serving as fearsome warriors in exchange for goods and taking the enemies of their associated human tribes as prey.

Wolgos even fought other Wolgos on behalf of their associated human tribes, evolving into a warrior caste. They were no longer separate and purely adversarial to the Eokoesr. Their lifestyle was completely transformed, leaping from a primitive existence with barely any tools to a people enjoying the benefits of agrarian and pastoral societies. They lived in relative luxury and were respected for their martial prowess.

Art and archaeological evidence from this era portray the Wolgos as an entirely martial caste, living close to humans but maintaining a distance and mystique. They jealously kept their women and children from human interference while enjoying all the trappings that came with their service. The Wolgos' evolution from primitive predators to a respected warrior caste marked a significant turning point in the history of the Dnkluwos Islands, laying the foundation for the complex societal structures that would follow.

As the Wolgos became more integrated with human tribes, their influence and numbers grew. They established themselves as protectors and enforcers, their fearsome reputation ensuring compliance and order within human settlements. Over time, the relationship between humans and Wolgos deepened, with the Wolgos often taking on roles that extended beyond mere mercenaries. They became arbiters of disputes, guardians of sacred sites, and, in some cases, leaders within human communities.

The symbiotic relationship between the Wolgos and the Eokoesr during this period was one of mutual benefit but also of underlying tension. The Eokoesr relied on the martial prowess of the Wolgos for protection and expansion, while the Wolgos depended on the resources and innovations of the Eokoesr to sustain their new way of life. This dynamic fostered a complex interdependence that would shape the social and political landscapes of Dnkluwos for generations.

This era, marked by the integration and collaboration of two distinct hominid subspecies, set the stage for the later development of the Dhonowlgos civilization. The blending of human ingenuity and Wolgos martial tradition created a unique cultural and societal framework that would define the future of the islands. The Wolgos, once on the brink of extinction, had found a new path to survival and prominence through their alliance with the Eokoesr, setting the foundation for the rise of a powerful and enduring civilization.

Calidus Era -4400 CE to -2400 CE and Wolgos Lordship Era -2400 CE 500 CE

As the Calidus climatic era began, it heralded the golden age of the Eokoesr lordships, transforming the Dnkluwos islands into a vibrant and prosperous region. During this period, the islands experienced their warmest climate, which facilitated the growth of new produce and introduced luxuries previously unknown to the region, such as wine. This new agricultural bounty supported the expansion of the Eokoesr lordships into petty kingdoms, where powerful kings ruled over numerous villages. Art flourished, with the construction of the first stone villages and the erection of impressive monoliths. The wealthiest petty kingdoms adorned their plastered walls with intricate painted scenes and motifs, reflecting their newfound prosperity, while pottery became increasingly elaborate, and metal forging emerged as a significant technological advancement.

The Calidus era brought about a period of relative peace and prosperity, but it also led to a degree of complacency and decadence. Despite their technological advancements, the Eokoesr society reached a plateau. As the society became more complex, its resilience waned. Petty kings and lords extracted increasing amounts of resources to sustain their opulent lifestyles, creating conditions that gradually eroded the system's stability. Unfortunately for the Eokoesr, the Calidus era was neither long-lasting nor permanent. After three hundred years of warmth and abundance, the climate began to cool once more.

As temperatures declined, failed harvests and a decrease in living standards ensued over the following centuries. Conflicts reignited, with the Wolgos once again fighting on behalf of the Eokoesr lords. However, unlike before, the Wolgos now had clear expectations that needed to be met. As conditions rapidly deteriorated due to the shock of decreasing temperatures, the Eokoesr lords were unable to fulfill the Wolgos' demands, leading to growing restlessness among the Wolgos warriors. This culminated in the Wolgos turning on their lords. Initially, these were isolated incidents, but eventually, more lords and petty kings were overthrown by their Wolgos warriors.

The Eokoesr upper echelons, having become reliant on the Wolgos for their military prowess, lost control within decades. By -2500 CE, the Wolgos leaders had usurped control from all Eokoesr lords and petty kingdoms. The Wolgos moved into human settlements, taking over meeting halls and palace roundhouses, transforming these into the first brochs of the Dnkluwos islands. These brochs served as symbols of Wolgos dominance, built to lord over the human villages from which they now extracted tribute.

As the Wolgos solidified their grip on the islands, they formed strategic alliances among themselves, minimizing internal warfare and increasingly extracting more from their human subjects. Over time, they replaced Eokoesr religious leaders with their own, supplanted Eokoesr scholars, artists, and craftsmen with Wolgos counterparts, and gradually increased their population. By -1000 CE, the upper Eokoesr echelon no longer existed, and all Eokoesr lived as peasants under Wolgos lords and knights. The Wolgos had become the entirety of the warrior, ruling, artisan, administrative, and priestly classes.

The cultural and artistic landscape of the Dnkluwos islands underwent a radical transformation. The Wolgos psyche, with its distinct set of values and aesthetics, took precedence, erasing human moral and artistic norms. Art began to reflect more gory, anatomical, violent, sexual, and mystical themes that were prominent in Wolgos culture. Human monuments and monoliths were altered, transformed, or demolished, replaced with art that celebrated Wolgos dominion.

Despite these drastic changes, the Eokoesr continued to live with a degree of dignity and had expectations of protection and justice from their Wolgos lords. They retained significant autonomy and freedom to live as their own people, albeit under the overarching authority of their Wolgos rulers. This era marked the complete integration and domination of the Wolgos over the Eokoesr, setting the stage for the development of the unique and complex society that would follow.

The rise of the Wolgos not only reshaped the social and political landscape of the Dnkluwos islands but also initiated a profound cultural shift. The Wolgos' emphasis on martial prowess and dominance infused every aspect of life, from governance to daily interactions. The Eokoesr, though subjugated, managed to maintain a semblance of their cultural identity, even as it was increasingly overshadowed by Wolgos influence. The Wolgos' control was not merely through brute force but also through a sophisticated system of cultural assimilation and dominance, ensuring that their rule was unchallenged and deeply entrenched in the fabric of society.

As the climate continued to fluctuate, the Wolgos demonstrated a remarkable ability to adapt, further solidifying their position. They utilized their understanding of both human and natural resources to maintain their stronghold over the Dnkluwos islands. Their strategic alliances, both within their ranks and with certain human factions, ensured a relatively stable rule despite the underlying tensions.

Prelude to Dhonowlgos and its Foundation 500 CE to 4000 CE

As the Proximal Ice Age set in and the Dnkluwos islands once more became colder, boreal, and harsher, the Wolgos lords sought to bolster their rule under increasingly difficult conditions. Wolgos technological advances allowed farming and pastoralism to adapt, but it nonetheless required sacrifices to be made—sacrifices that fell on the Eokoesr. This marked the true commencement of the Eokoesr's plight and subjugation.

Rebellions and conflicts against increasingly harsh Wolgos lords led to brutal reprisals. Peasants became serfs, and serfs became slaves as conditions deteriorated. The Wolgos' tendencies toward the most extreme and effective solutions quickly eroded the Eokoesr's autonomy and humanity. Nevertheless, the lordships suffered from constant conflicts with each other, as highland and northern lordships moved south seeking more temperate conditions and encroached on each other's territory.

For a time, the disparate lordships seemed on the brink of not surviving the worsening conditions, with total conflict appearing imminent. Fortunately for Wolgos society, a parallel power structure had developed over centuries from the priestly classes—a structure that transcended the borders of the lordships and united the Wolgos under the faith of the god Dlrocha. Temples existed and were united through extensive networks that transcended borders, sharing knowledge and culture and providing mediation for conflicts between lords.

The Upeh₂sterh₂ekm Conclave of 3010 CE took place during the middle of the Proximal Ice Age, a conclave brought about by the temple monks who convinced the majority of lords to attend a central location where the future city of Dhowkros would be founded. The conclave, conceived as a meeting to demarcate lordships and bring about unity to the lands to achieve a shared commonwealth and ensure the survival of the Wolgos people, lasted five months and resulted in the founding of Dhonowlgos. The name means "flow/run of the voice that comes," but it can be better translated as "the Continuity of the Sacred Voice."

Though poorly understood currently, it is clear that arranging the conclave took a complex array of strategies and schemes by the temples to force the lords to come together. It took great leadership skills by monks now lost to history and great feats of guile, manipulation, and Machiavellian politics to bring about the conclave, especially considering its outcomes.

The outcome resulted in the elevation of the temples into abbeys with lands donated by lords to the abbeys. These abbeys would moderate the lords' politics and ensure fairness and stability, providing record keeping, administration, trade centers, and banking for the lords. The abbeys came together as Circles of Faith under a grand council whose sacred duty became to interpret celestial will and direct the faith of the islands and guide the lords.

The foundation of Dhonowlgos was a landmark moment, uniting all the Wolgos for the first time in history. Its founding led to instant peace across the lands. Lords settled grievances in courts, personal duels, or orchestrated ceremonial battles overseen by monks and designed to minimize damage. The mistrusts of the lords with their armies came to a head in 3155 CE after a series of machinations by lords against monastic rule and their allies, resulting in the obliteration of the rebel lords. To prevent future threats against monastic rule, lords were, by celestial guidance, forced to forgo their private armies. Instead, they were forced to send their homosexual men, who they would not miss, to the abbeys to join a new order—the Hlrike. Founded in 3156 CE, the Hlrike became the nation's military, holding the sole monopoly on force in Dhonowlgos.

The Hlrike not only centralized military power but also provided a unifying force that reinforced the theocratic and monastic rule. These developments ensured that the Wolgos society became more structured and stable, with a clear separation of religious, political, and military power, all under the guiding influence of the abbeys. The Eokoesr, however, continued to suffer under the increasingly institutionalized subjugation, their plight worsening as the Wolgos society advanced and consolidated its power.

Life for the Eokoesr under Wolgos rule was harsh and unforgiving. The Wolgos, with their penchant for absolute solutions, implemented brutal measures to ensure control and maximize productivity. The Eokoesr were not merely subjugated; they were increasingly dehumanized, treated as little more than livestock. Their lives were dictated by the needs and whims of their Wolgos masters. The serfs worked the land, toiled in mines, and served in households under grueling conditions. Their status was hereditary, passed down from generation to generation, with little hope for escape or improvement.

Despite the harshness of their existence, pockets of resilience and defiance emerged among the Eokoesr. Secret traditions and cultural practices were maintained, passed down through whispers and coded messages. In some remote areas, the Eokoesr were able to maintain a semblance of autonomy, living in close-knit communities that supported one another.

The Wolgos, for their part, viewed the Eokoesr as a necessary but inferior part of their society. They implemented a rigid caste system that kept the Eokoesr firmly at the bottom, with no chance of upward mobility. The Wolgos' sense of superiority was reinforced by their religious and cultural practices, which emphasized their divine right to rule. The monastic rule provided a veneer of legitimacy to their dominance, with the abbeys and Circles of Faith acting as both spiritual and temporal authorities.

The abbeys played a crucial role in maintaining this system of oppression. They provided the ideological and administrative framework that kept the Wolgos society running smoothly. Through their control of education, religious instruction, and record-keeping, the abbeys ensured that the Wolgos' version of history and culture was preserved and propagated. The abbeys also acted as mediators and arbiters, resolving disputes between lords and ensuring that the Eokoesr remained subservient.

Relative Isolation 3000 CE to 5200 CE

Between the 3000s and 5200s, Dhonowlgos largely existed in seclusion, isolated from the rest of Gotha. The Wolgos had little notion of the world beyond their shores and for hundreds of years seldom ventured outwards. The monks maintained an inward focus, believing the Dnkluwos islands to be the sole collection of large land bodies atop an ocean sphere called Gotha. They perceived the far-flung coasts they had heard of as mere sandbanks circling the Dnkluwos archipelago.

By the early 5000s, a new phenomenon began to occur. Fishermen started detecting other vessels venturing into the waters of what the Wolgos believed was their world-spanning empire. These foreign and strange vessels were heavier and less sleek than the Wolgos' small longships and struck great panic across the echelons of monastic rule. The monks feared these ships might be spirits or, worse, foreign peoples from lands they had no idea existed.

In 5203, one of these mysterious ships lost its course after a terrible tempest in the stormy sea and ran aground on the shores of Dhonowlgos. The ship, the Silubrōna Fethara, was an early coastal cog belonging to the Orkanan Realm of Stoldavia. The crew was rescued by bewildered Wolgos farmers who were both intrigued and shocked to see Eokoesr-looking people as the crew of such a strange ship. News spread quickly, and by nightfall, the Hlirke and delegates from the local Kulher’ghem abbey had arrived to inspect the wreckage and foreign crew.

Scribes and engineers from the abbey thoroughly investigated the wreckage, finding all manner of documents written in a strange and incomprehensible language, drawings, maps, artifacts, and a ship of strange design. The Hlirke and monks attempted to question the crew but found their language incomprehensible. Both the shipwreck and crew were taken to Dhowkros, where the shipwreck was carefully studied by mystics and monk scholars, who determined it to be of mundane and not celestial origin. They also learned new engineering techniques from it. The crew itself was kept a secret and held for years at the Dhowkros Hlirke compound to avoid causing a commotion throughout the nation. The deep suspicion and panic caused by the crew led scholars to teach them the Wolgos language and to decipher Old Stoldish, the first foreign language heard by anyone in the Dnkluwos islands in millennia.

Unfortunately for the Stoldish, once the Wolgos gained a way of communicating with them and extracting all they could through amiable means, they turned to torture to validate all they had learned from the crew. None of the twenty-four rescued crew members survived the months of interrogation and torture that ensued. Nevertheless, the Wolgos learned of a much wider world. They gained detailed knowledge of Stoldavia and Jorveh and vague knowledge of lands beyond Stoldavia. They also learned how to improve their shipbuilding techniques.

For the next two centuries, paranoia gripped Dhonowlgos, and a large fleet of improved and much larger longships, the likes of which had never been built before, was commissioned. The size of the fleet was determined blindly out of fear of an unknown potential foe. The Wolgos began to cautiously sail further out to the shores of Stoldavia, mapping them, hunting for errant ships in longship packs. Sometimes they feigned friendship and called on small villages, trading or kidnapping Stoldish people to learn more about their now-known potential foes.

Era of Exploration and Defense 5300 CE to 7000 CE

From the 5300s to the 7000s, Dhonowlgos oscillated between exploration and defense of their homeland. During this era, Dhonowlgos' increasingly sophisticated longships explored the coasts of northern Anaria, reaching as far south as the Scavic Peninsula, Grey Coast, and Refuge Bay across the Stolvic Ocean. Despite these exploratory endeavors, Dhonowlgos never managed to outmaneuver the existing powers in these regions, such as the Orkanan Realm and the Second Stoldavian Empire. The lands explored by Dhonowlgos were often under the influence of the Stoldish or other powers like the Aldgesian.

Dhonowlgos itself remained an enigma, closed off and mired in mystery for outsiders. Direct contact with the nation was rare and minimal. Overtures from foreign dignitaries were consistently refused, and only the Wolgos themselves traveled occasionally to Stoldavia and other lands for feigned diplomacy before disappearing again, often for years or decades. During these rare interactions, they would ask numerous questions, purchase books and artifacts, and occasionally kidnap people, leading to soured diplomatic relations. Stoldavia attempted to invade Dhonowlgos on three separate occasions, with the last invasion by the Second Empire in 7105, all of which were successfully repelled by Dhonowlgos' increasingly sophisticated fleet.

During this era, the Wolgos managed to establish whaling outposts on Piqsuk and Siku islands in the Landsight Archipelago. These barren and uninhabited islands, home only to seabird colonies and patches of hercy mosses and lichens, became crucial to the first Wolgos trek in the upcoming centuries. These outposts were dependent on fishing and imports for their sustenance.

Colonial Expansion and Fall of the Second Stoldavian Empire 7000 CE to 7400 CE

The fall of the Second Stoldavian Empire allowed Dhonowlgos to expand without engaging in warfare. As the empire crumbled, Dhonowlgos quickly seized the opportunity to take over its nascent colonies on the Jaw Coast, Surom Land, and Refuge Bay in Stoldavia. By the late 7200s, the Wolgos had taken over these Stoldish settlements, claiming they had been abandoned. In reality, the Hlirke had clandestinely captured the Stoldish colonists and enslaved them, fabricating evidence that native Altaians were responsible for the settlements' demise.

Paradoxically, while Dhonowlgos was expanding, it remained largely secluded from foreign nations and powers. The Wolgos flexed their naval might as a deterrent but avoided direct conflicts, maintaining a distance from the outside world. The fragmented state of Stoldavia in the 7300s allowed the Wolgos to focus on their New Xedun colony, favored for its remote location and the arctic seas that shielded it from the direct interest of other powers. New Xedun, with its boreal climate, temperate fringes in the south, and dry steppe landscape beyond the coasts, was unattractive to other colonial nations but suited the Wolgos.

By the start of the 7400s, the New Xedun colony had expanded to encompass Refuge Bay, Cold Lip, Icy Throat, and the southern foothills of the Threshold Rise. The colony's population grew to almost two million Wolgos and Eokoesr, living in stereotypical Wolgos villages and building an agrarian and pastoral economy. Exports to Dhonowlgos consisted of timber, furs, whale products, and fish, with ores only becoming significant towards the collapse years of Dhonowlgos.

The exploration and defense era marks a critical phase in Dhonowlgos' history, where the nation balanced isolation with cautious expansion. The Wolgos' strategic use of their naval capabilities and their careful management of external threats ensured their dominance in the region. However, this period also set the stage for future conflicts and the eventual transformation of Wolgos society as they interacted more with the outside world.

Raids on Stoldavia 6000 CE - 7200 CE

For almost twelve hundred years, the Wolgos occasionally raided Stoldavia and, to a lesser extent, Nestor. the raids were the work of state-sanctioned coastal communities who were permitted to build large longships and to sail beyond the permitted waters. These were purely profiteering raids to bring gold, luxuries, slaves, and humans as food and other commodities. These raids were essential in keeping Dhonowlgos up to date with the advances beyond its shores, and often, centres of learning such as Orkanan monasteries were targets.

Pan-Anarian War 7422 CE to 7499 CE

- See also: Pan-Anarian War

Dhonowlgos was thrust into a war by Helreich through a calculated use of gunboat diplomacy. Helreich, wielding its superior navy, blockaded Dhonowlgos from its colony and harassed its coasts, compelling the nation to acknowledge Helreich's demands. Enticed by promises of territorial gains and technology transfers, Dhonowlgos reluctantly joined the conflict. The alternative was a devastating bombardment of their coastal towns and colonial transfer fleet by the Helreich navy.

In the first two years, Dhonowlgos engaged in minor skirmishes, using this period to upgrade its military and fleet with Helreich technology and tactics. The Hlirke warriors quickly distinguished themselves on the battlefield, demonstrating their formidable prowess. By the fourth year, Dhonowlgos was operating independently on a larger scale, culminating in the invasion of the Vindkysten coast—a region where Helreich had reached a stalemate.

The Wolgos forces advanced through the Blue Mountain Ridge, pushing deep into Mörenburg and opening these regions to Helreich annexation. They expanded their operations to distant regions like Nestor and Thulthania, but their brutality soon became a significant concern. Helreich and its allies grew increasingly suspicious of the Wolgos, who showed a blatant disregard for the rules and morals of war. The Vindkysten coast suffered catastrophic losses, with over sixty percent of its population perishing due to Wolgos brutality and scorched-earth tactics.

In Mörenburg, the capital city was besieged and flattened, with its monarchy publicly executed and cannibalized by Wolgos generals. The citizens of Mörenburg endured widespread brutality, rape, and mutilation. The Wolgos' refusal to take prisoners and their habit of collecting skulls as trophies outraged the Anarians and other observers.

Controlling the Wolgos proved nearly impossible for Helreich. The Wolgos, from the lowest ranks to the highest command, looked down upon all non-Wolgos, leading to frequent conflicts with Helreich command. The Hlirke warriors insulted and treated Anarians with disdain, never relinquishing their arrogance. They resented working alongside humans and often caused intentional friendly fire incidents.

The tipping point came after the Mörenburgish king and his family were publicly executed and cannibalized by Wolgos generals. The devastation left by the Wolgos in the conquered territories caused an outcry for justice from the survivors. In 7499, Helreich and its allies had enough. Secretly, they conspired to turn against Dhonowlgos, leading to the sudden onset of the Haverist-Wolgos War.

The betrayal was swift and brutal. Overnight, Helreich and its allies launched coordinated attacks against Wolgos positions, aiming to curb the chaos and restore order. The once-allied nations now found themselves in a bitter conflict, determined to end the Wolgos' reign of terror. This new phase of the war was marked by intense battles and a shared resolve among Helreich and its allies to bring justice to the war-torn regions, marking a significant turning point in the history of Dhonowlgos and its imperial ambitions.

Haverist-Wolgos War and Destruction 7499 CE to 7504 CE

First Wolgos trek 7504 CE to 7514 CE

- Main article: First Wolgos Trek

The First Wolgos Trek was a monumental migration of the Wolgos people, driven by the desperate need to survive following the defeat of Dhonowlgos in the Helreich-Wolgos War (7499–7504), a conflict instigated by their actions during the Pan-Anarian War and once the plight of the Eokoesr became public. Relinquishing their ancestral lands to the Häverists under a peace agreement, the Wolgos embarked on a harrowing decade-long exile marked by resilience and hardship.

The evacuation began amidst the devastation of Dhonowlgos, where overwhelming Helreich air and naval forces destroyed cities and forced the Wolgos leadership to relocate civilians, cultural artefacts, and military forces. In the initial 14 months, women, children, and essential personnel were transported to the New Xedun colony via improvised fleets, braving treacherous seas and harsh weather. This first wave set the stage for the larger, gruelling migration that followed over five years.

The second phase involved thousands of overloaded ships of diverse varieties traversing the Stolvic Ocean. Convoys that frequently faced storms, ice, disease, and internal conflicts. In Altaia, the native Telwotti populations of northern Altaia fiercely resisted the influx, escalating the hardships faced by the refugees and, which resulted in the decimation of the Telwotti as the Wolgos, as a response, hunted them down as food. The overland journeys through the icy Landsight Peninsula compounded the Wolgos' trials. Entire convoys of refugees were lost to snowstorms and the bitter cold of the north. Colonial ranger waystations located in the northern wilderness served as crucial but strained sanctuaries, and the Hlirke provided vital protection and logistical coordination.

Despite immense suffering and loss, the Wolgos' and Hlrike resilience conquered the adversities of the trek. By 7514 CE, the industrialized colony of New Xedun had balloned into state in the making ready to conquer the Altaian wilderness, becoming the centre of Wolgos culture and governance. This migration laid the foundation for the Bind, the Hlirke dictatorship that would direct Wolgos society for the next century, cementing their survival and identity after one of their darkest eras.

Geography

- Main article: Dnkluwos Islands

The Dnkluwos Islands, situated at the northernmost reaches of Anaria just north of Stoldavia, are separated by the tempestuous and stormy sea. These islands exhibit a dynamic climate heavily influenced by the celestial phenomenon known as the tyreal maximum and minimum. This cycle dictates periods of abundance and scarcity, weaving a rhythm of life intertwined with the islands' natural beauty. The largest island, characterized by contrasts and natural wonders, is slowly being torn apart by a tectonic plate boundary, giving rise to the Cinder Plains. This region, marked by volcanic activity, features warm stone badlands, boiling rivers, volcanic cones, steam vents, geysers, and frequent seismic tremors, creating a harsh yet flourishing environment for a variety of well-adapted flora and fauna. Since the dawn of the industrial era, the Cinder Plains have been a crucial source of energy, initially exploited by the indigenous Wolgos people and later by the Eokoesr.

Historically, a land bridge, now submerged, connected the Dnkluwos Islands to the mainland of Stoldavia, transforming them into a peninsula characterized by shifting sandbars, brackish marshlands, and seasonal submersion. This land bridge, now over twenty meters underwater at its shallowest point, stands as a testament to the earth's ever-changing face. Although reconnecting the islands to the mainland via a hypothetical bridge has been proposed, active geological movements make such a project unfeasible. The climate and geological features of the Dnkluwos Islands are profoundly shaped by the tyreal cycle, which affects temperature, glacier coverage, and the course of rivers, reshaping valleys and promoting biodiversity. The flora and fauna have adapted to these climatic shifts, with species like the highland ironwood, cinder pines, and the haiter giant elk thriving across the varied landscapes. The islands' biomes range from temperate valleys and old-growth forests to the volcanic Cinder Plains, showcasing the remarkable adaptability and resilience of nature.

The diverse climate and geological features of the Dnkluwos Islands have given rise to unique ecosystems. The flora includes resilient species like the highland ironwood, cinder pines, and coastal burgundy cedar, each adapted to their specific environments, from highlands and wetlands to volcanic plains and coastal areas. The fauna, equally diverse, features the majestic haiter giant elk, highland wolves, and the robust highland bears, each playing a crucial role in maintaining the ecological balance. The volcanic regions host specially adapted species like the geothermal snakes and steaming river fish. These islands, with their unique blend of temperate valleys, boreal forests, and volcanic plains, showcase the remarkable adaptability and resilience of nature, forming a vibrant and complex web of life.

Government

Central to the framework of Dhonowlgos' governance is a meticulously constructed tapestry woven from the threads of theocratic monastic rule, mysticism, and authoritative governance. The nation's political landscape is uniquely defined by a federation of monastic holdings known as dh'hghsleyghes, colloquially referred to as abbeys. These abbeys transcend mere administrative units; they serve as the lifeblood of Wolgos nation for centuries, presiding over towns, villages, and fertile farmlands.

Dh'hghsleyghes - Abbeys

At the core of Dhonowlgos' governance, abbeys were the governing entities for distinct territorial divisions, whether expansive or localized. Each abbey functioned as a governing body, steering the course of its domain. Overseeing the hierarchies of the abbeys was the elected high monk, known as Diushweg. Though the formalities of election were observed, the ascent of a Wolgos monk to the revered Diushweg position was a tale of intricate maneuvering, a display of religious and academic prowess, and diplomatic finesse.

The hierarchy of abbeys encompassed roles as the local administration, civil service, and spiritual guides. In a symbiotic pact, the inhabitants of an abbey's territory contributed tribute, whether currency or a portion of their harvest. In return, the abbeys extended protection, religious guidance, and administrative stewardship. Rooted in Wolgos society, the authority of the abbeys was derived from a blend of religious doctrine, witchcraft, and even violence. Notably, tyrannical behavior, as perceived by human standards, was an exception rather than the rule. The aura of power and might that abbeys projected sufficed to maintain their dominion.

Hghsbh’hendh – Circle of Faith

Abbeys, differing in size and influence, formed a collective symphony, culminating in the establishment of regional Hghsbh’hendhes, or Circles of Faith. These circles were presided over by a Whloerra, a Diushweg whose ascent, through democratic means, elevated them as the most equal among equals. Rooted in a spirit of collaborative governance, the circles focused on harmonizing economic policies, nurturing the growth of the crucial Eokoesr labor force, and fostering seamless coordination between administrative units. In essence, the circles aimed to cultivate a unified governance structure that transcended individual abbeys.

Komh’hergh – Council of Circles

The Council of Circles, a harmonious assembly of Whloerra monks representing their respective circles, emerged as the legislative heart of the nation. Beyond its legislative duties, the council bore the mantle of directing and coordinating national policies. However, its most sacred role was the interpretation and observance of the will and prophecy of the enigmatic Vlroicha. This solemn responsibility formed the cornerstone for the guidance of both the Council of Circles and the upper echelons of Wolgos governance.

Dlricho

Interwoven into Dhonowlgos' framework were the mysterious Dlricho. Unlike their counterparts tied to specific abbeys, the Dlricho found their abode in secluded compounds, nurtured by the benevolence of the state. These mystics, endowed with prophetic abilities, communion with the spirits of creation, and visions, added an extra layer of enigma. The Dlricho were drawn from Wolgos who exhibited the mystic psychosis – a fairly common condition. Once inducted into the Dlricho order, they were nurtured and submerged in religious doctrine, allowing them to explore their mystical talents fully. The prophecies and visions of the Dlricho were treated as revered omens, frequently consulted by abbeys. The unraveling of the mysteries within these insights often prompted extensive efforts to decode Dlrocha's intentions.

Vlroika

At the pinnacle of faith and the Council of Circles stood the foremost Dlricho monk, the Vlroika. Through a journey marked by rigor, devotion, and spiritual insight, the Vlroika personified the highest echelons of earthly authority among the Wolgos, second only to the spirits of nature and Dlrocha. The presence of the Vlroika within the Council of Circles carried weight universally acknowledged, wielding influence that directed decisions and held the power of veto. Deciphering the will of Dlrocha through the perspective of the Vlroika was no facile endeavor, often requiring the counsel of scholars specialized in mysticism. While some edicts and vetoes might have seemed counterintuitive, they were met with solemn respect, acknowledging the Vlroika's unique conduit to the divine realm.

Administrative Divisions

Dhonowlgos was an intricate theocratic federation, a tapestry woven from religious, economic, and military threads. This unique societal structure revolved around a network of abbeys, federated into regional governments, all under the legislative umbrella of the Komh’hergh.

Abbey System - Dh'hghsleyghes

The core of Dhonowlgos's societal structure was its abbeys, known as Dh'hghsleyghes. These were not merely religious sanctuaries but multifaceted institutions that managed extensive territories. Each abbey oversaw farmland, controlled resource exploitation, and governed a population tasked with agricultural and commercial production.

The economic sustenance of Dhonowlgos heavily relied on the output of these abbeys. Farmers working the abbey lands contributed a portion of their harvest as a tax, creating a sustainable agrarian economy. Additionally, commercial activities within the abbey's territories were taxed, providing a steady income stream. Administrative fees for various services further bolstered the abbeys' financial resources.

Beyond economic management, abbeys functioned as regional administrative centers. They were responsible for local governance, maintaining civic order, and providing basic services to their inhabitants. The integration of Hlirke Brocks, military units, within the abbey structure was crucial. These units protected the abbey's territories and enforced its decrees, ensuring compliance and security within their jurisdictions.

Regional Governance - Hghsbh’hendh

The Hghsbh’hendh, or Circles of Faith, served as regional governments within Dhonowlgos. Each circle comprised a federation of abbeys, pooling resources and administrative capabilities. Dominated by the more affluent and strategically located abbeys, these Circles were instrumental in regional governance.

The Hghsbh’hendh's primary role was in economic and political management. They collected taxes and produce from their constituent abbeys, redistributing these resources to ensure regional prosperity. Their ability to resell goods and produce across the nation played a significant role in stabilizing the national economy.

Legislative Authority - Komh’hergh

The Komh’hergh, or the Council of Circles, was the legislative heart of Dhonowlgos. Funded by the Hghsbh’hendh, it crafted policies and laws that guided the entire federation. The Komh’hergh’s decisions were paramount, ensuring that the collective interests of the abbeys and, by extension, the nation were met. This council symbolized the unity of the abbeys under a single legislative framework.

The economic structure of Dhonowlgos was ingeniously designed to sustain both the religious and military facets of the state. The Hghsbh’hendh not only managed regional affairs but also funded the Komh’hergh and the Hlirke Command. This funding was crucial for the maintenance and expansion of the Hlirke’s military capabilities, including the navy and the military industries. It ensured that Dhonowlgos remained secure and could project its power when needed.

Colonial Empire

Law and Order

Demographics

| Wolgos | Eokoesr |

|---|---|

| Population: 14,292,846

Demographic Breakdown

Gender Ratio and Age Distribution

|

Population: 9,528,564

Demographic Breakdown

Gender Ratio and Age Distribution

|

Wolgos Social Classes

- Monks and High Priests

- Description: The spiritual and political leaders of the Wolgos society, High Priests were responsible for overseeing religious practices, rituals, and the management of abbeys and the state. They wielded the strongest influence over both the spiritual and temporal aspects of life in Dhonowlgos, interpreting the will of Dlrocha and guiding the populace and government policy.

- Lifestyle: High Priests lived in abbeys, dedicating their lives to religious service, study, and the administration of their monastic holdings. They were revered figures, often involved in the arbitration of disputes and the implementation of social policies.

- Tribal Nobility

- Description: The tribal elite of Dhonowlgos, the Tribal Nobility were the largest landowners after the monastic establishment. They controlled large estates, held significant political influence, and were responsible for maintaining order and stability within their domains. Their wealth came from vast land holdings and the labour of the Eokoesr who worked these lands. They lived in grand estates and were deeply involved in the social fabric of the nation and held significant sway in the governance of the nation.

- Lifestyle: Their lives are marked by luxury and opulence. They engage in political manoeuvring, manage their estates, and participate in elaborate social and religious ceremonies. Education and training in leadership, strategy, and governance are paramount.

- Hlirke Monks

- Description: A distinct class within the monastic system, the Hlirke Monks were composed of all Wolgos homosexual men who serve both religious and military roles. They were known for their strict discipline and dedication, arcane practices, balancing monastic duties with martial training and service.

- Lifestyle: Living within their own broch compounds, Hlirke Monks engaged in rigorous training and religious study, were not celibate. They formed close-knit communities, contributing to the defence of Dhonowlgos and the enforcement of religious doctrine.

- Deacons (Priests with Families)

- Description: Priests who were allowed to marry and have families, Deacons served in local communities, providing spiritual guidance and performing religious ceremonies. They bridged the gap between the monastic elite and the general populace.

- Lifestyle: Deacons lived among the people they serve, maintaining households and participating in community life. They were responsible for teaching, conducting religious services, and offering pastoral care.

- Merchants and Artisans

- Description: Skilled tradespeople and business owners, Merchants and Artisans were the backbone of the Dhonowlgos economy. They produced high-quality goods, such as pottery, textiles, furniture, tools, machinery and weapons, and engage in trade and formed part of a burgeoning class of industry owners with wealth rivalling the tribal nobility.

- Lifestyle: Living in urban centers and market towns, they enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle relative to their skill and success. Their workspaces were integral to the economy, and they often passed their skills down through generations.

- Skilled Workers and Overseers

- Description: This class included professionals, managers, clerks, engineers and supervisors who work in various sectors, including industry and agriculture. They oversaw the work of Eokoesr laborers, ensuring productivity and efficiency.

- Lifestyle: Skilled Workers and Overseers lived in modest but comfortable homes. Their roles required a blend of technical knowledge and managerial skills, and they often underwent specialized training.

- Small Landholders (Farmers)

- Description: Independent farmers who owned and work their own land, Small Landholders contributed significantly to the agricultural output of Dhonowlgos. They operated smaller farms compared to the estates of the Tribal Nobility but were self-sufficient and vital to local food production.

- Lifestyle: These farmers lived in sturdy, well-built homes and work alongside their families. Their lives were marked by hard work and community involvement, with a focus on sustainable farming practices and self-reliance.

Eokoesr Social Divisions

- Rural Agricultural Workers

- Description: Eokoesr laborers working on small farms, often in gruelling and oppressive conditions. They were essential for maintaining the agricultural productivity of Dhonowlgos, performing tasks such as planting, harvesting, and tending to livestock.

- Lifestyle: Despite their status, Rural Agricultural Workers lived in relatively better conditions compared to other Eokoesr classes. They had modest rustic homes to inhabit, some personal possessions, and could maintain family units. Their lives involved long hours of physical toil but with a semblance of stability and respect.

- Farm State Workers

- Description: Eokoesr employed on large state-owned and Nobility-owned plantations. These farms were more regimented and controlled, with Eokoesr laborers subjected to strict oversight and demanding work schedules.

- Lifestyle: Conditions were often harsher than on smaller farms, with workers living in crowded barracks and performing backbreaking labour. They were closely monitored and have even fewer freedoms than rural Eokoesr.

- Industrial Workers

- Description: Eokoesr employed in factories, mills, and other industrial settings. Their work involved manual labour, such as operating dangerous machinery, conducting hard monotonous work and handling raw materials.

- Lifestyle: Industrial Workers live in densely populated barracks attached to their factories and workshops, often in squalid conditions. They faced constant danger from the machinery and hazardous materials, with little regard for their safety or well-being.

- Town Laborers

- Descriptio': Eokoesr working in urban areas, performing menial tasks essential to the daily functioning of towns and cities. Their duties included cleaning, waste management, hauling goods, and other low-status jobs.

- Lifestyle: Town Laborers lived in cramped lock-ups, often chained and under strict supervision. Their lives were marked by high stress, exposure to every facet of Wolgos life and society, and the constant threat of punishment.

- Civic Laborers

- Description: Eokoesr assigned to maintain and work on infrastructure projects, such as bridges and monuments. They often lived in extremely poor conditions, providing a source of amusement and a visual reminder of Wolgos dominance.

- Lifestyle: Civic Laborers endured public humiliation and harsh physical labour. They were forced to beg for food and trinkets from passersby, their suffering seen as a form of grotesque art by the Wolgos.

Society

- Main articles: Wolgos of Dhonowlgos and Eokoesr of Dhonowlgos

Social structure

Traditions

Religion

Education

Economy

- Main article: Economy of Dhonowlgos

The economy of Dhonowlgos was complex and multifaceted, characterized by a blend of agricultural, pastoral, artisanal, and industrial activities. This economy was deeply intertwined with the hierarchical social structure, religious practices, and the utilization of the Eokoesr labor force. Agricultural production formed the foundation of the economy, with fertile lands dedicated to the cultivation of staple grains and vegetables. Pastoral activities complemented agriculture, involving the raising of livestock such as aurochs, sheep, and poultry, which provided essential meat, dairy products, and wool. Artisanal crafts and industries, including textile manufacturing and metalwork, flourished due to the skilled labor of the Wolgos artisans. Meanwhile, the industrial sector, marked by the use of steam technology, drove the production of goods and fueled the economy, especially around resource-rich areas like the Cinder Plains. The monastic institutions, through their abbeys, played a pivotal role in managing economic activities, acting as both spiritual and economic hubs that controlled large tracts of land, oversaw production, and facilitated trade. The Eokoesr labor force, subjected to harsh conditions and strict oversight, was essential to the economic productivity, performing the most menial and grueling tasks that sustained the agricultural, pastoral, and industrial sectors.

Agriculture

Agriculture formed the backbone of the Dhonowlgos economy. The fertile lands, especially during warmer periods, were used to cultivate a variety of crops. These included staple grains such as wheat, barley, and oats, as well as root vegetables like Anarian potatoes, carrots, and sweet potatoes, alongside other vegetables like cabbage, cucumbers, and asparagus. Agriculture was primarily conducted by Eokoesr laborers under the supervision of Wolgos overseers and landowners.

The pastoral economy was equally important. The Wolgos raised various livestock, including aurochs (a breed of large cattle), sheep, pigs, and poultry. These animals provided meat, dairy products, wool, and leather. Pastoral activities were integrated into the agricultural cycle, with livestock helping to fertilize fields and provide labor for plowing and other tasks. Eokoesr also played a significant role in tending to livestock, managing daily tasks like feeding, cleaning, and milking.

Unlike other Anarian societies, the Wolgos in Dhonowlgos farmed arthropods. The Naesslor beetle grub was the chief source of protein. Large tracts of land were dedicated to willow coppicing to feed the grubs kept in large aerated barns where they grew to around six inches in length before harvesting. Other unique livestock included earthworms and mice, both popular in various Wolgos meals.

The fishing, seal, and seabird farming industries were critical to the economy of Dhonowlgos, providing a significant amount of stable food across the nation. The Wolgos preferred to preserve and ferment their fish rather than consume it fresh, allowing them to store and transport their produce across the islands.

Artisanal and Craft Economy

The Wolgos had a rich tradition of craftsmanship, producing high-quality goods such as pottery, textiles, furniture, tools, and weapons. Artisans were highly respected, and their workshops were integral to both the local and wider economy. These workshops often produced goods not only for local use but also for trade across the nation.

The Wolgos cuisine, which included a variety of preserved meats, fermented foods, and aged cheeses, supported a thriving artisanal food industry. Fermented milk drinks, strong spirits, and other unique beverages were produced in significant quantities, contributing to both local consumption and trade.

Industrial Economy

The industrial sector of Dhonowlgos was marked by the use of steam technology. The Cinder Plains, with their steam pipelines, were central to this sector. These pipelines supplied steam to textile mills, machining workshops, and other industries. The maintenance and expansion of this steam network were crucial for industrial productivity. Eokoesr laborers, under the harsh supervision of Wolgos overseers, were responsible for the grueling and hazardous work of maintaining these pipelines.

Textile manufacturing was a major industry, with mills producing various fabrics and clothing. Machining workshops produced tools, fittings, building and structural goods, weapons, and other metal goods. Industrial activities were concentrated around resource-rich areas, with the Cinder Plains being a hub for steam-powered industries, leading to the growth of new settlements.

Trade and Commerce

Internal trade was robust, with goods moving between rural and urban areas. Agricultural products, livestock, artisanal goods, and industrial products were traded extensively. Marketplaces in towns and cities were bustling centers of commerce, where the Wolgos and Eokoesr interacted within the strict confines of their social hierarchy.

Dhonowlgos, while relatively isolated, engaged in limited external trade. Goods such as textiles and crafted items were traded with neighboring regions. The Wolgos' advanced shipbuilding skills allowed them to explore and engage in limited but significant trade, bringing in foreign goods and ideas that occasionally influenced their economy. The vast majority of foreign trade occurred with its colony of New Xedun, with trade with foreign nations exclusively occurring in foreign ports. Dhonowlgos strictly forbade all foreign ships from calling at their ports or approaching the islands.

Labor Economy

The Eokoesr were the backbone of the labor economy. Their roles ranged from agricultural and pastoral work to menial industrial and resource extraction tasks. The Eokoesr were treated as property, with their labor heavily exploited under harsh conditions. They performed the most menial and grueling tasks, often under constant fear and threat of severe punishment. Their labor was essential for maintaining the economic productivity of Dhonowlgos.

The Wolgos, particularly the males, dominated skilled labor and management roles. They were artisans, overseers, industrial workers, professionals, and traders. Wolgos females, while less involved in direct economic production, contributed through roles in medicine, education, and domestic management.

Monastic Influence

The abbeys and monasteries played a central role in the economy, acting as both spiritual and economic hubs. They controlled large tracts of land, overseeing agricultural production, and managing artisanal workshops. The abbeys also functioned as banks and trade centers, providing loans, minting currency, storing surplus produce, and facilitating trade.

Religious practices and festivals stimulated economic activity. Pilgrimages, offerings, and religious festivals required goods and services, creating demand for various products. The abbeys collected tributes and tithes, redistributing wealth through investment in infrastructure, administration, and community projects, while retaining significant resources to maintain their influence.

Military

Notes

| Wolgos Sub-species | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Physiology topics: Wolgos Psyche - Wolgos Development From Birth to Adulthood - Death for the Wolgos - Wolgos Sexuality - Wolgos Masculinity - Wolgos Womanhood | |||||

| Historic and current Nations of the Wolgos | |||||

| Dhonowlgos | The Bind | Hergom ep swekorwos | United New Kingdoms | ||

|

|

||||

| ~3000 CE - 7505 CE | 7508 CE - 7603 CE | 7608 CE - Present | |||

| History & Geography |

History of Dhonowlgos: History of Dhonowlgos - Stained Era - Era of Rising Lilies

|

|---|---|

| Politics & Economy |

Dhonowlgos Politics: Politics - Foreign Relations

|

| Society & Culture |

Dhonowlgos Society: Monuments - Society - Brochs of Dhonowlgos

|

| History & Geography |

History of The Bind: History - Geography - Military - Science - Brochs of The Bind

|

|---|---|

| Politics & Economy |

Politics of The Bind: Politics - Military - Administrative Divisions of the Bind

|

| Society & Culture |

Society in The Bind: Brochs of The Bind - communication in The Bind - Demographics

|

| History & Geography |

History of The United New Kingdoms: History

|

|---|---|

| Politics & Economy |

Politics of The United New Kingdoms: Politics - Military

|

| Society & Culture |

Society and Culture in The United New Kingdoms: Wolgos Culture in the UNK - Demographics - Humans of the UNK

|