Wolgos

| Ethnic group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

' | |||

| Height comparison | |||

| |||

| Eye colour |

| ||

| Hair colour and type |

| ||

| Total population | |||

| Location map | |||

| |||

| Regions with significant populations | |||

| Missingflag.png?nolink&40 test Missingflag.png?nolink&40 test | |||

| Languages | |||

| Religions | |||

| Related ethnic groups | |||

| [[ ]], [[ ]] | |||

Etymology

The endonym "Wolgos," used by the Wolgos hominid subspecies, signifies "Willed Ones," a name that is deeply rooted in their faith and divine origin. The term encapsulates the essence of the Wolgos as beings who were willed into existence by their deity, Dlrocha. This profound act of creation is reflected in their name, which combines elements that emphasize their divine purpose and the powerful will of Dlrocha. The name "Wolgos" is not merely a self-referential term but a declaration of their unique genesis and spiritual destiny.

According to the teachings of Dlroch'veldr, the Wolgos were created through the deliberate and powerful will of Dlrocha, manifested during the mystical union of Dlrow and L’cha. This divine act imbued the Wolgos with a special purpose and a spiritual mandate, setting them apart from other beings. The concept of being "Willed Ones" underscores their belief in a preordained mission guided by the visions and teachings of their deity. The Wolgos' identity is thus intertwined with their faith, with each individual perceiving their existence as a direct result of Dlrocha's will. This spiritual understanding fosters a deep sense of duty and community, as the Wolgos believe they are part of a divine plan, endowed with resilience and purpose to fulfil their sacred path. Through this lens, the name "Wolgos" embodies their collective and individual journeys, marked by divine will, spiritual fortitude, and an unwavering commitment to their deity's guidance.

However, due to their unique psyche and the inherent discord between Wolgos and humans, the Wolgos often find themselves at the receiving end of pejoratives. These derogatory terms frequently reference their distinct albinism, a characteristic that visually sets them apart. The Wolgos' pale skin, white hair, and red or lilac eyes, while a source of cultural pride and identity, also make them targets for scorn and prejudice from humans who misunderstand or fear their differences. Terms such as "ghosts" or "pale devils" are commonly used by humans, reflecting deep-seated xenophobia and the inability to bridge the vast psychological and cultural gap between the two species. This alienation is further exacerbated by the Wolgos' complex emotional and moral landscape, which often starkly contrasts with human norms and values.

History

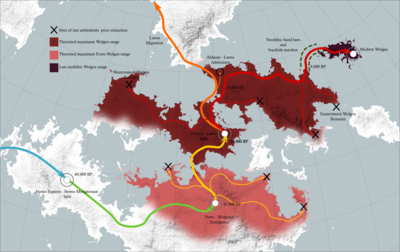

Around sixty thousand years ago, Homo Merignosian diverged from their Homo sapiens counterparts, representing a distinct pre-Wolgosid hominid lineage that bore a striking resemblance to humans in many ways. This separation marked the initial steps toward the emergence of the Wolgosids, a subspecies known for their unique physiological and psychological characteristics.

Approximately thirty thousand years ago, a significant turning point occurred in the reproductive compatibility between Wolgosids and humans. Reproduction between these two groups became largely incompatible, resulting in exceedingly rare successful pregnancies. The intricacies of this incompatibility remain a subject of ongoing scientific investigation, with only around one in 230 attempts at conception yielding viable results.

Around the same period, roughly thirty thousand years ago, the schism between the Luora and Wolgosids began to take shape. Albinism, although not universally observed, was already becoming a prevalent trait among the Wolgosids. This genetic divergence marked the initial stages of their unique path of evolution.

Fast-forwarding to sixteen thousand years ago, the Stoldavian Wolgosids had undergone a significant transformation. Albinism had become a universal trait among them, setting them apart from their ancestral roots. Archaeological evidence from this period hints at their deep integration into a predatory lifestyle focused on humans, shaping the dynamics of their interaction with other hominids.

During this time frame, the Thulthanian Wolgosids, once a distinct branch of this subspecies, faced extinction. Roughly fourteen thousand years ago, their existence became a relic of the past, leaving a lasting mark on the evolutionary tapestry of Wolgosids.

By the dawn of the last ice age, around nine thousand years ago, the Wolgosids were on the brink of extinction. Their population dwindled to a mere handful, clustered in the region of the now-submerged Stjerneo peninsula. Their survival hinged on their interaction with human tribes, as they traversed the eroded land bridge that once connected Stoldavia and the Greater Dunkluwos island.

As time progressed, approximately eight thousand years ago, the Wolgosids faced a turning point. With rising sea levels, they became separated from their Stoldavian origins, isolated on the Dunkluwos islands. Here, their population began to thrive, influenced by their predatory behavior towards human tribes.

Six thousand years ago, the Wolgosid way of life underwent transformation, leading to a resurgence in their numbers. Gradually, their population expanded beyond the mere thousands, solidifying their dominance among the hominids of Dunkluwos.

Anatomical and biological characteristics

The Wolgos subspecies exhibit several distinct biological characteristics that set them apart from humans. Over thousands of years of adaptation, they have undergone physical changes, sexual dimorphism, and alterations in their microbiome, all in response to their unique Neolithic survival strategies and the harsh environment the subspecies experienced in the era before civilization.

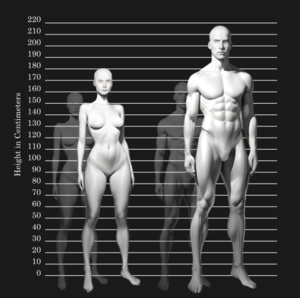

One remarkable feature of the Wolgos is their significant sexual dimorphism. The average height of Wolgos men is approximately 7 feet, while Wolgos women reach an average height of 5'10 feet. Wolgos males are usually far stronger than their female counterparts and have physical builds ideal for brute and violent confrontations. Their musculature is denser, with broad shoulders, thick limbs, and pronounced muscle definition, all contributing to their intimidating presence. These physical attributes were essential for their roles as hunters and protectors within their communities, enabling them to overpower prey and rivals with sheer force.

Females, while closer in size to humans, were equally adapted to their roles in the Wolgos' survival strategies. Their strengths lie in surviving adverse conditions, with metabolisms suited to enduring long stretches of hunger and cold. They have a voluptuous, curvy build, providing them with greater fat reserves to sustain themselves and their offspring during times of scarcity. This physical adaptation also facilitated their roles in nurturing and safeguarding young Wolgos, ensuring the continuation of their lineage even in the harshest of environments.

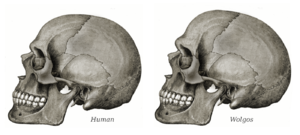

The Wolgos' skull is somewhat thicker than that of humans, providing additional protection against trauma. Their cranial bones are more robust, and their skulls are designed to withstand significant impact. This adaptation likely evolved to protect them during violent confrontations and falls. Additionally, the meninges of the Wolgos, the protective membranes surrounding the brain, are thicker and slightly more spongy. This unique characteristic further enhances their ability to withstand stronger blows than most humans, reducing the risk of concussions and other traumatic brain injuries.

These physical adaptations, combined with their social structures and survival strategies, have enabled the Wolgos to thrive in environments that would be challenging for other species. Their significant sexual dimorphism, robust cranial structure, and specialized metabolisms highlight the evolutionary pressures they faced and their remarkable ability to adapt and survive.

Denture and microbiome

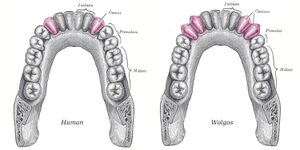

Their denture is similar to that of humans but with some notable differences. Wolgos possess a unique trait of having double sets of canines on the upper and lower denture rather than a single pair like humans. These canines have deeper roots, are thicker, and are marginally larger than those of humans, providing them with a more robust bite. This feature allows them to exert greater force when biting, essential for their predatory lifestyle.

Behind the back set of canines lies the first premolar, which is pointier and more canine-like in form. This premolar is flatter widthwise, designed more for a slicing action than grinding. The subsequent premolars also follow this slicing design, enhancing their ability to tear through flesh and hold onto prey more securely. These adaptations are thought to have evolved to help their ancestors tear the flesh of human carcasses with ease and to hold onto prey with a bite more securely.

Their molars are very human-like, except for the furthest back set of wisdom teeth, which in humans often cause discomfort and need removal. In the Wolgos, there is a second set of wisdom teeth that are weaker in structure and invariably become impacted and cracked. While these can cause discomfort at first, they serve a crucial function. As the gums settle, these impacted teeth cease to cause inflammation and act as a bacterial reservoir for the Wolgos' oral microbiome.

The Wolgos have also undergone changes in their microbiome, resulting in a symbiotic relationship between their oral, gut, and skin bacteria and their survival strategies. One notable example is the bacteria present in their mouths, which have an increased pathogenic ability to cause septicemia in humans they might bite. This adaptation conferred an advantage to the Wolgos' ancestors, as it allowed them to cause debilitating illnesses by biting during confrontations. This made it easier to track down human prey that escaped or even caused their death, allowing the Wolgos to scavenge human carrion.

Additionally, certain bacteria found in their oral microbiome produce metabolites similar to scopolamine, a potent substance known for its mind-altering and manipulative effects. While the Wolgos are immune to these metabolites, they can use their saliva to compromise human targets by ensuring it comes in contact with epithelial tissues in places like the eyes, mouth, and nose. By doing so, the Wolgos can make their prey more pliable and suggestible. In the Neolithic era, this was often used to turn their target into a lure that could entice their kin or tribe members into a Wolgos ambush. This trait is often used to this day for a wide range of purposes, including the development of a way of speaking that promotes the formation of saliva aerosol with the hope of compromising the faculties of the humans they are speaking to. In general, as long as there is no close or intimate contact between humans and Wolgos, this trait is of no concern to humans.

Albinism

The most striking characteristics of the Wolgos are their complete and universal albinism. Wolgos have pale white skin devoid of any pigmentation, resulting in an extremely fair complexion that stands out starkly compared to humans. This albinism extends to their hair, which is entirely white, whether it grows on their head or elsewhere on their bodies. Their eyes are another defining feature, typically appearing in shades of red or light lilac due to the lack of pigment. This absence of pigmentation affects not just their appearance but also their interaction with their environment, particularly with regard to sunlight.

Albinism in Wolgos is not merely a cosmetic trait; it has profound implications for their health and survival. Their lack of melanin, which is responsible for protecting the skin from ultraviolet (UV) radiation, makes them highly susceptible to the adverse effects of sun exposure. When exposed to direct sunlight, Wolgos can suffer from painful welts, burns, and, with prolonged exposure, the risk of developing cancerous growths increases significantly. This vulnerability to UV radiation has shaped many aspects of Wolgos culture and lifestyle.

To mitigate the harmful effects of sunlight, the Wolgos have developed various strategies and practices. They often go to great lengths to prevent sunburns and other ill effects of sunlight. For example, they predominantly live in regions with dense forest cover or areas that naturally provide shade and protection from direct sunlight. Their architecture and settlements are designed to minimize exposure to the sun, with structures that provide ample shade and indoor spaces that are cool and dark.

Wolgos clothing also reflects their need to protect their skin. They wear garments made from thick, tightly woven fabrics that cover most of their bodies, including long sleeves, high collars, and wide-brimmed hats. These clothes are not just functional but have also become a part of their cultural identity, often adorned with intricate designs that reflect their heritage. Additionally, they use natural substances and ointments with sun-blocking properties, derived from plants and minerals, to coat their skin when they must be outside during the day.

Their daily routines and activities are also adjusted to avoid peak sunlight hours. The Wolgos are predominantly nocturnal or crepuscular, preferring to conduct their activities during the twilight hours of dawn and dusk or under the cover of night. This behavioural adaptation reduces their exposure to harmful UV rays and allows them to thrive in environments where sunlight is less intense. Their night vision is superior to that of humans, allowing them to function effectively in low-light conditions, which is an evolutionary response to their need to avoid sunlight.

Socially, the impact of albinism extends to how the Wolgos interact with one another and with other species. Their pale, almost ethereal appearance has often been a source of fear and myth among human populations, leading to numerous legends and folklore about ghostly beings in the forests. Within their own communities, the Wolgos take pride in their unique appearance, seeing it as a mark of their identity and resilience. This perception has also influenced their standards of beauty. The Wolgos consider their pale skin, white hair, and distinctive eye colours to be the epitome of beauty, often regarding these traits as symbols of purity and strength. This internal standard of beauty reinforces their cultural pride and cohesion, further distinguishing them from other species.

Despite these adaptations, the threat of sun exposure is a constant concern for the Wolgos. They have developed a cautious and strategic approach to their environment, always mindful of the sun’s position and the availability of shade. This vigilance is a necessary aspect of their survival, ingrained into their daily lives and cultural practice.

Characteristic Scent

Their microbiome differences combined with strong sexual dimorphism have led to a noticeable characteristic often observed by humans: Wolgos men, in particular, possess a deep and strong musky scent that persists even after thorough washing or attempts to mask it with perfume. This distinctive scent is described by humans who interact with them as similar to the smell of someone who has recently engaged in vigorous exercise. However, it also contains hints of body odour that are unfamiliar and distinctly non-human.

This musky scent is a result of the unique composition of the Wolgos microbiome, particularly the bacteria present on their skin. These bacteria produce compounds that contribute to the distinctive smell, which is a blend of pheromones and other metabolic by-products. For the Wolgos, this scent is familiar and normal to the point of being imperceptible among themselves. However, humans find it to be quite strong, and it can impregnate fabrics and even rooms, lingering long after the Wolgos have left.

Humans who come into close contact with Wolgos often find the scent intriguing yet slightly unsettling due to its intensity and unfamiliarity. It reinforces the otherness of the Wolgos and can invoke a mix of curiosity and caution. The musky odour, combined with the Wolgos' physical presence and unique appearance, contributes to the overall perception of them as formidable and enigmatic beings.

Vision and gaze

The Wolgos possess a distinctive gaze that often appears aloof and uninterested, a direct result of their unique visual adaptations. Due to their albinism, Wolgos suffer from constant, involuntary eye movements known as nystagmus. These micro-movements cause their eyes to continuously shift, preventing stable eye focus. However, their brains have adapted to this by averaging out the visual input, creating a stable image despite the constant motion. This neural adaptation compensates for the lack of stable eye focus, allowing the Wolgos to maintain attention on objects or individuals through advanced neural processing rather than direct eye movements.

Despite these adaptations, the overall vision of the Wolgos is still subpar compared to humans. They struggle particularly with photosensitivity, finding bright light conditions uncomfortable and challenging to navigate. Their eyes continuously replace damaged photoreceptor cells to maintain retinal health and visual acuity, but this rapid turnover does not fully compensate for their heightened sensitivity to light.

The combination of neural processing and nystagmus gives the Wolgos a gaze that seems diffuse and unfocused, even though they might be intently focused on an object or person. Observers often notice the micro-movements of their eyes, reinforcing the impression that the Wolgos are not directly engaged. This visual appearance can be perceived as disinterest or aloofness, which affects how they are seen in social interactions, especially by non-Wolgos.

Within Wolgos culture, this distinctive gaze is interpreted differently. It is often seen as a symbol of control and composure, reflecting the Wolgos' ability to maintain stable visual perception despite their constant eye movements. This capability is viewed as a demonstration of inner strength and mental acuity. The Wolgos rely on other non-verbal cues, such as subtle facial expressions, body language, and vocal tones, to convey their attention and engagement, which are crucial for effective communication within their society.

In day-to-day activities, Wolgos face both challenges and advantages due to their unique vision. They underperform in activities requiring prolonged exposure to bright light, such as daytime navigation or outdoor tasks, and they might struggle with detail-oriented tasks like reading small print. However, they excel in low-light conditions, where their vision adaptations give them a significant advantage. They are highly effective in nocturnal navigation and stealth, leveraging their enhanced peripheral vision and neural processing capabilities. Additionally, their advanced visual processing skills make them adaptable in roles requiring situational awareness and pattern recognition.

Genetics

The Wolgos exhibit a unique genetic profile that significantly distinguishes them from humans. One of the most striking genetic traits of the Wolgos is their complete and universal albinism. This results from the loss of several melanin-producing genes, and the few that remain are non-functional. This genetic anomaly is responsible for their pale white skin, completely white hair, and red or light lilac eyes. Their lack of melanin places them at a disadvantage when exposed to sunlight, often leading to painful welts, severe sunburns, and a higher incidence of skin cancer. As a result, the Wolgos have developed extensive strategies to protect themselves from the sun, including nocturnal lifestyles and wearing protective clothing.

Another significant genetic difference between Wolgos and humans lies in their chromosomal structure. Wolgos have a total of 45 chromosomes, one less than humans, who have 46. This difference is due to the fusion of two ancestral chromosomes into a single, larger chromosome in the Wolgos karyotype. This fusion has created a pair of chromosomes that is much larger than any found in humans, which complicates reproductive compatibility between the two species.

Reproduction between humans and Wolgos is extremely difficult and rare. The differences in chromosome number and structure often result in infertility or non-viable offspring. When hybridization does occur, the resulting hybrids face significant genetic challenges. These hybrids might display a mix of physical and genetic traits from both parents, but they are typically sterile, similar to mules resulting from horse and donkey crosses. The sterility is due to the mismatched chromosomal pairing during meiosis, which prevents the formation of viable gametes.

The reproductive physiology of the Wolgos is adapted to their unique lifestyle and environment. Wolgos females have reproductive cycles that are slightly longer than those of human females, and their fertility peaks under conditions of reduced stress and ample resources. The gestation period for Wolgos is similar to that of humans, lasting around nine months. Wolgos new-borns develop at a rate comparable to human infants, but they are typically more robust and resilient in their early stages of life.

Genetic diversity within Wolgos populations has been a concern due to their historically insular and concentrated populations, as well as the loss of large population segments due to past wars. Despite these challenges, the Wolgos do not manage genetic lines actively; instead, they allow natural selection to take its course. A stark aspect of their cultural practices is that defective new-borns are not allowed to grow up. This practice, intended to maintain the health and strength of their population, is similar to some historical human practices of infanticide based on physical defects.

Disease and congenital conditions

The Wolgos for most of their ancient neolithic history numbered in the hundreds and as a result of inbreeding have always suffered as a subspecies from carry over of congenital changes and conditions unique to the subspecies. As their numbers have increased the conditions are less of a risk to their survival but remain a thorn in their biology and health care.

Articulatio Doloris Primitiva, commonly known as ADP, is a congenital ailment that affects the lives of some Wolgos. This condition, rooted in intricate genetic interactions, ushers in a life of joint inflammation and chronic pain. From early stages of life, ADP silently entwines itself around the affected individual's joints, inflicting a barrage of discomfort. ADP launches an inflammatory onslaught on the joints crucial for mobility and activity. As the joints swell and ache, even the simplest movements become burdensome tasks. The condition's impact is not confined to discomfort; it gradually corrodes essential joint components like meniscuses and cartilage. The result is a profound deterioration in joint function, accompanied by excruciating pain.

Cutis Fragilis Solaris, commonly referred to as CFS, is a complex ailment intricately linked to the albinism prevalent among the Wolgos subspecies. This condition manifests as an autoimmune response to the ultraviolet (UV) light that streams from the very sun they encounter daily. Wolgos with CFS bear skin that is astonishingly sensitive to touch, leading to a phenomenon akin to the shedding of fragile petals. Even the gentlest contact can trigger the separation of the epidermal layers, leaving behind a raw expanse vulnerable to infection and discomfort. CFS manifests as a direct response to the body's attempts to shield itself from the UV radiation that penetrates their pale dermal layer. An immune reaction unfolds, wherein the skin's delicate balance is disrupted, leading to the fragility that characterises CFS.

Carbostrangulatus Syndrome hijacks of some Wolgos' ability to efficiently process carbohydrates. Instead of smoothly extracting the life-sustaining energy from these vital nutrients, their metabolism stumbles, leading to a cascade of dire consequences. The syndrome emanates from a defective enzyme critical for carbohydrate breakdown, subjecting the Wolgos to a chronic energy deficit. The symptoms of Carbostrangulatus Syndromes mirror the relentlessness of the condition itself. Sufferers endure an unceasing fatigue that defies conventional rest. Mundane tasks become feats of monumental exertion as their bodies grapple with generating energy for even the most rudimentary movements.

Labbrocorruptio Syndrome, arising from a genetic mutation among the Wolgos, disrupts their symbiotic relationship with their oral microbiome. Their mouths become battlegrounds as an overactive oral biome attacks their weakened defences. Even minor injuries lead to raw, infection-prone areas, triggering chronic inflammation, degradation, and rot. This condition compromises their immune response, rendering them susceptible to secondary infections, while chronic inflammation distorts facial features and can lead to deformities. The heightened risk of oral cancer looms ominously.

Wolgos Psyche

The Wolgos psyche is significantly different from the main Gothan hominid, humans. Wolgos tend to appear to share traits common to human psychopathic personalities, The Wolgos' sense of empathy is nothing like that seen in your average human, and it is often said to be lacking, but in reality, what can be described as a sense of empathy in the Wolgos is weak, shallow, strategic and with a narrow focus to those that provide them with an advantage, for they care for their offspring, family and tribe but even then their empathy is shallow and largely exists to fulfil base biological instincts such as reproduction, safety and support.

Otherwise, Wolgos empathy is tenuous at best, especially with those outside their peer circles, outsiders, or outside their ethical framework. During the wars of the past where nations fought against the Wolgos, no single example of mercy, empathy and sympathy that was not a ruse or a cunning ploy was documented. If fact, there are numerous anecdotes of the Wolgos responding to humans in distress or in terror with amusement, curiosity or, at best, indifference; it was not uncommon for Wolgos soldiers to toy with prisoners or defenceless civilians who would, in due course, meet a slow and unfortunate end. The Wolgos, despite numerous negotiation attempts, never adhered to or were willing to understand the international codes for civilised war, despite never respecting human dignity. Paradoxically the Wolgos were outraged when members of their subspecies were mistreated.

Different expression of fear and guilt

To the astonishment of their adversaries, the Wolgos, when disadvantaged or in mortal danger, do not react as humans would; their sense of fear is different, and they never seem to panic or display common behaviours expected of feeling terrified. The Wolgos, when experiencing what can be described as fear, tend to either go very quiet, observant and calculative or become enraged and berserk. Even though they do not experience fear in the same way as humans, they are able to feign such emotions if they feel they can manipulate their opponents.

As seen by many anthropologists and people that deal with the Wolgos, the Wolgos are skilled at appearing charismatic, pleasant and charming, but those that deal with them consistently often learn there is little depth or sincerity to their charm. Their charisma is often a tool of persuasion and manipulation and will slip when they feel it's not warranted or when their aims and intentions change. They can be cold and callous with those they feel are beneath the effort of being charming or who they control, and they have no qualms about being egregious or intimidating. They can be said to enjoy intimidating others.

Their sense of guilt and remorse is weak, and they do not experience distress from such emotions; when they do experience it, anthropologists often describe it as more like a sense of hindsight accompanied by mild unease and concern. Their sense of responsibility for their actions is highly dependent on their individual interests, those of their immediate social circle of interest, and their own kind.

Unique communication and ethics

An aspect of their psyche that causes great discord with humans is their innate deceitful and manipulative nature; the Wolgos are well known to easily create intricate webs of lies, stories and falsehoods to manipulate others and advance their interests. For humans, in general, it's hard to trust and honestly communicate with the Wolgos; even in mundane interactions, the Wolgos will find opportunities to slowly construct a web of deceit to advance their interests or make the other more pliable if they were to need them in the future. This aspect is universal even when interacting with other Wolgos. Still, members of the Wolgos subspecies have a deep understanding of their own deceptive nature to the point that they regard deception as a social mannerism while simultaneously being able to communicate the truth between the lines of their deceptive speech intentionally or unintentionally to other Wolgos who are easily able to read between the lies.

This unique communication style, where deceptive speech and actions are ingrained in their social interaction, relies on a nuanced understanding of implicit messages and subtext, allowing them to communicate important information while maintaining a veneer of deception. Metaphors, symbolism, and indirect communication are prevalent and essential in their interactions.

Despite these traits, the Wolgos have a deep sense of mutual understanding. They seemingly find a mutual synergy with each other and form successful social groups and societies; their mutual understanding is heavily reinforced by their strong inclination to follow intricate social codes and rituals to navigate their deceptive tendencies. These codes serve as a means to express trust, build alliances, and identify shared goals or hidden intentions.

The Wolgos gravitate towards developing a strict ethical framework favouring the ingroup and facilitating cooperation and interaction. These frameworks often form part of their mystical and religious belief systems or local traditions; they help to provide shared interests that align their actions and interactions. As a minority of Wolgos males have an inclination to develop traits similar to mystical psychosis, the Wolgos have a strong affinity towards superstitions and towards mystical notions, Wolgos often interpret mystical visions and altered states of consciousness as direct connections to powerful spiritual entities, guiding the society in its survival strategies or offering divine insight. Many often believe that those with mystical insight have access to a higher truth or understanding that transcends the ordinary reality perceived by others.

Physical inhibitions

The Wolgos exhibit a distinctive psychological trait that sets them apart from humans—a lack of inherent mental inhibitions against causing harm, even in situations where humans would typically restrain themselves. Unlike humans, who often overcome such inhibitions in extreme circumstances, the Wolgos do not possess these innate barriers. Comparable to their primate relatives, such as chimpanzees, the Wolgos act without the subconscious restraints that hinder the infliction of harm. Whether engaged in physical combat or attempting to cause damage, they operate with an unimpeded focus and dedication, similar to problem-solving. This trait translates to their fights and harmful actions being executed with maximum strength and proficiency, often resulting in significant damage. This perception of uninhibited strength and efficacy is deeply ingrained in their psyche, making them formidable opponents in their own view, even though their physical strength is similar to that of humans.

Psyche sexual dimorphism

Wolgos psyche traits are more strongly represented amongst the male members of the subspecies; female Wolgos tend to be far more empathic even though their empathy is generally focused on their offspring, partner, family and kin. Women often provide a counterbalance to their male equivalents, and their nurturing qualities foster stronger social cohesion and a release of tension. Wolgos men can grow to form a dependence on their female partners, where they depend on their undivided attention and nurture to soothe their often grandiose egos.

Nevertheless, the disparity in traits leads to male-dominated hierarchies and relationships where women face reduced agency, male traits invariable lead to their domination of relationships. Power dynamics play a significant role in their romantic relationships. Males often seek to establish and maintain dominance, utilising manipulation, control, and calculated tactics to assert their influence, while females tend to seek to create dependence and help males rationalise an emotional connection to cement a romantic relationship beyond superficial infatuation.

Sexual dynamics and manipulation are prevalent in their romantic relationships. Sexual interactions can be used by females as a means of asserting some control and exploiting vulnerabilities in their partners. Males are more interested in fulfilling desires and urges but can easily apply a similar strategy to further their intentions.

General and Romantic Attachment

The Wolgos, despite sharing some traits with individuals who exhibit psychopathic and sociopathic tendencies, possess a distinct pattern of attachment and social interaction that sets them apart from strict categorizations of these disorders. While they are capable of forming attachments, the nature and intensity of these attachments differ significantly from those observed in mainstream human populations. Many of these characteristics are believed to be linked to the X chromosome, resulting in varying manifestations between Wolgos men and women.

Wolgos men exhibit an intensified form of attachment formation, characterized by a focused and selective approach. Their strongest and most intense attachments are typically reserved for their primary caregivers, often their mothers, and later in life, their romantic partners. They perceive their offspring as a direct extension of themselves, leading to profound attachments. Beyond these primary circles, their attachment-forming tendencies become increasingly tenuous, if not altogether absent. Close peers and extended family members are the outermost boundaries of their attachment sphere.

In contrast, Wolgos women exhibit a broader range of attachment formation, which aligns more closely with the patterns observed in mainstream humans. They form attachments in a manner akin to humans, with a strong emphasis on peers, social groups, and extended family. However, when it comes to romantic attachments, Wolgos women tend to exercise caution. They often resist advances from males, projecting an aloof and dismissive demeanour to discourage premature attachment formation. This can sometimes lead to complications, especially if a male becomes infatuated despite a lack of reciprocal interest. Wolgos men, on the other hand, tend to form intense and impulsive attachments when they perceive female interest, which can spark conflicts among protective parties or rival males vying for a relationship.

Despite the intensity of their romantic attachments and potential competition for mates, Wolgos males exhibit a distinct style of romance that diverges from mainstream human norms. Their expressions of romance are characterized as possessive, controlling, and selfish, with sporadic and restrained displays of affection. While Wolgos males may feign romantic behaviours during the courtship phase, they view these actions as means to an end rather than intrinsic expressions of affection. The burden of engineering romantic gestures often falls on Wolgos females, who expect to take the initiative in eliciting expressions of romance.

Both Wolgos men and women exhibit a robust sense of in-group and out-group dynamics, with a strong affinity for their in-group depending on the specific context, such as working environments, clans, tribes, or hominid groups. They display a natural inclination toward exclusion and are prone to developing negative preconceptions of out-group members, a tendency that researchers have consistently observed in their social interactions.

Maternal Bonds

Wolgos children, especially boys, forge exceptionally strong and enduring bonds with their primary caregivers, typically their mothers. These maternal relationships are profound and resilient, extending throughout their lifetimes. They are characterized by a depth of emotional connection rarely seen in mainstream human societies.

From infancy, Wolgos mothers take on a highly protective and nurturing role, diligently tending to their children's needs. They provide not only physical care but also emotional support and guidance. Mothers are known for their unwavering devotion, often doting on their offspring well into adulthood.

The maternal attachment is a source of emotional security and stability for Wolgos children. If severed, these bonds evoke intense if rare Wolgos expressions of grief and loss.

Paternal Influence

While fathers among the Wolgos also play essential roles in their children's lives, their style of caregiving differs from that of mothers. Fathers tend to maintain a more detached stance, especially during the early stages of a child's life. This detachment can occasionally manifest as subtle resentment toward their offspring, stemming from the attention and care they receive from their mothers.

However, as Wolgos children grow and mature into productive members of the family or clan, their relationships with their fathers often undergo a transformation. Fathers become more involved and engaged, offering guidance, mentorship, and protection. The loss of a father figure can lead to varying expressions of loss and grief, nevertheless they can be as strong as that of the loss of a mother depending on the strength of the paternal relationship.

Wolgos Mannerisms

Speech Mannerisms

The Wolgos converse with a methodical precision that resembles a well-rehearsed performance. Each word is deliberately chosen, articulated with an exactness that borders on the unnatural. This meticulous approach to speech often strips away the spontaneity and warmth typically found in human dialogue. Their conversations, though fluent, carry an undercurrent of something being carefully staged or performed.

In their interactions, the Wolgos exhibit an unsettling blend of charisma and emotional detachment. They can engage in discussions with a charm that seems practiced and somehow superficial. This veneer of amiability, however, is undercut by a lack of genuine emotional engagement. Their expressions of empathy or concern often appear as if learned from a script, lacking the authentic emotional resonance one might expect.

The Wolgos' conversations are laced with a subtle undercurrent of control and manipulation. They navigate dialogues not just to communicate but to subtly influence and direct the flow of interaction. This manipulation is not overtly domineering but rather manifests as a skilful orchestration of conversation, where they seem to always be a few steps ahead, anticipating and subtly guiding responses.

Despite their seemingly casual demeanour, there is an intensity to the Wolgos' focus in conversations. They often give the impression of analysing every response, weighing words with an almost clinical detachment. This intense scrutiny, hidden behind a façade of casual conversation, can be disconcerting, as it feels like nothing said is trivial or escapes their notice.

While the Wolgos generally maintain a controlled and methodical approach in their communication, there are moments when an unexpected intensity breaks through their composed exterior. These bursts might manifest as a sudden sharpness in their tone, a piercing gaze, or an emphatically delivered phrase. This sporadic intensity, often seemingly accidental and quickly subdued, adds a layer of unpredictability to their interactions.

These occasional displays of intensity stand in sharp contrast to their usual demeanour, making them all the more striking. One moment, they might be engaging in a conversation with their characteristic cool detachment, and the next, they might exhibit a flash of anger, excitement, or fervour, before swiftly returning to their usual controlled state.

For human interlocutors, these unpredictable shifts can be disquieting. The sudden departure from the Wolgos’ usual composed and methodical speech to a brief yet intense emotional display can be jarring, leaving an impression of a complex and somewhat volatile inner world.

Emotional Landscape of the Wolgos

The Wolgos possess a complex emotional spectrum, but their experiences and expressions of certain emotions differ markedly from those of humans. Emotions that are typically positive in humans, like love, joy, and pleasure, often carry additional layers in the Wolgos. For example, what humans would recognize as love may manifest in the Wolgos as a blend of intense obsession, possessiveness, and a deep-seated desire for control. Their expression of joy might be tinged with an undercurrent of superiority or even aggression, rather than pure elation.

In social contexts, the Wolgos often exhibit a fascinating blend of emotions. A conversation that starts with genuine interest might subtly shift to a display of superiority or subtle dominance. Their laughter, while genuine, may carry a hint of sarcasm or even a sense of enjoyment at another's expense. This duality makes their social interactions multi-layered and often perplexing to outsiders.

Relationships, especially romantic ones, are intense and deeply passionate. However, this passion is frequently intertwined with a desire to possess or control their partner. Love in the Wolgos’ world is a complex emotion, where deep affection coexists with a strong sense of ownership and often jealousy. This blend of emotions results in relationships that are both deeply fulfilling and inherently intense.

The Wolgos thrive in situations of conflict and competition. They derive a significant amount of pleasure from besting others, whether in intellectual debates, physical contests, or social manoeuvring. This isn’t merely about the joy of winning; it’s also about the satisfaction of asserting dominance. In their professional lives, this trait makes them formidable adversaries and astute strategists.

Expressions of joy and pleasure in the Wolgos are complex. They experience these emotions intensely, but often these feelings are heightened by an underlying negative emotion. For example, the joy of success is amplified not just by the achievement itself but by the defeat or subjugation of rivals. Pleasurable activities might be laced with elements of control or even sadism, blending enjoyment with darker undertones.

Less intense emotions like mild annoyance, amusement, or curiosity are expressed with a subtlety that can be easily missed or misinterpreted by humans. These expressions require a nuanced understanding of the Wolgos' non-verbal cues, which are often elusive to human observers.

Facial Expressions of the Wolgos

The facial expressions of the Wolgos are a complex interaction of fleeting cues and subtle shifts. A momentary tightening of the lips or an almost imperceptible narrowing of the eyes can convey volumes, hinting at a thought process or emotional response that belies their composed exterior. These micro-expressions are brief but revealing, offering glimpses into their multifaceted inner world that is often masked by a more neutral or controlled façade.

The Wolgos' faces frequently display a fascinating contrast between their attempted expressions of warmth and the underlying intensity of their true emotions. A smile, intended to be reassuring, might be undermined by a coldness in their eyes, or a look of empathy might be contradicted by a rigid set of the jaw. These contrasts create a sense of dissonance and unpredictability in their interactions, as their true feelings occasionally seep through the carefully maintained exterior.

Their gaze is particularly telling, capable of shifting from a deeply engaging, almost invasive intensity to a distant, detached look within moments. This variability not only makes it challenging to gauge their focus and interest but also adds an element of unpredictability to their demeanour. The intensity of their gaze, when it does lock in, can be unsettling, as it often feels too probing, too analytical, almost as if they are peering into one's very thoughts.

In lighter moments, the Wolgos might display a playfulness in their expressions, but these moments are frequently tinged with darker undertones. A playful smirk might quickly turn sardonic, or a gleam of amusement in their eyes might have a hint of cruelty. These subtleties serve to remind that their emotions and thoughts are complex and often not as straightforward as they might initially seem.

The Wolgos are particularly adept at masking their more intense negative emotions, but signs of anger, disdain, or scorn can still manifest briefly on their faces. These emotions, though quickly controlled, can leave a lingering impact, hinting at the depth and intensity of feelings that lie beneath their controlled exterior. The speed with which they conceal these emotions speaks to their awareness of how they are perceived and their desire to maintain a certain image.

Emotional Resilience

The Wolgos display an almost innate resilience to emotional traumas that typically affect humans. Their experiences with violence, whether in conflict or other circumstances, do not seem to inflict the psychological scars often seen in humans. Post-traumatic stress, a common human reaction to intense or prolonged violence, is virtually unknown to them. This resilience can be attributed to their distinct psyche, which processes such experiences in a fundamentally different way.

For the Wolgos, memories of conflict often hold a different sentimental value compared to humans. Veterans of battles may recall their experiences with a sense of nostalgia, reminiscing about them as if recalling adventures or spirited exploits. The loss of comrades, while acknowledged, is remembered without the profound sadness or grief typically exhibited by humans. Instead, there is a fond acceptance, a sort of fond reminiscence that lacks the emotional weight of sorrow or regret.

In situations that would typically induce fear or panic, the Wolgos maintain a remarkable composure. Their response to fear is notably different – instead of panic or flight responses, they might exhibit a heightened focus, aggressiveness, risk taking, a sharp clarity of thought that allows them to navigate through threatening situations effectively. This response can be disconcerting to observe, as it contrasts sharply with typical human reactions to fear, but that its not to say that the Wolgos are fearless but that this is the way they express fear. The Wolgos describe similar feelings of rushing adrenaline and tension much like humans do in such situations.

Even in high-stress situations, the Wolgos’ emotional responses, often perceived as a strength, can come across as unsettling or even inhuman to those unfamiliar with their ways.

Life stages

Childhood

As experienced by the Haeverist of Helreich, Wolgos children pose a unique challenge for humans when it comes to upbringing. From an early age, they exhibit traits such as impulsiveness, callousness, and occasional outbursts of intense anger. To understand and successfully nurture Wolgos children, caregivers employ distinctive strategies deeply rooted in Wolgos culture.

Wolgos parents introduce responsibility to their offspring at a young age, often assigning tasks, routines, and even productive endeavours. It's not uncommon to witness Wolgos children actively participating in family businesses or taking on small "jobs" as part of their upbringing. This approach aims to instil a sense of accountability and purpose early in life.

Play among Wolgos children serves as a valuable tool for teaching them to control their impulses, manage anger, and grasp the concept of consequences. Interestingly, Wolgos society doesn't discourage physical confrontations in their games but rather encourages them. These games provide a controlled environment where children learn the boundaries of acceptable behaviour, discover the repercussions of their actions, and forge friendships through shared experiences. Such games, although intense and sometimes leading to scuffles, help Wolgos children navigate their inner callousness. As Wolgos boys mature, their games tend to shift from rough play toward more cooperative and structured activities. These groups of boys often form small gangs, engaging in collective endeavours or business ventures. While their youthful mischief persists, it gradually transforms into organized pursuits.

In contrast, Wolgos girls embrace a different avenue for social development. They master the art of storytelling, engage in gossip, and build close bonds with other girls. The responsibility they assume within their households is met with dedication and enthusiasm, and they take pride in the recognition they receive. Wolgos girls often establish traditional yet practical enterprises such as crafting quilts, embroidery, or providing repair services to earn both income and a sense of responsibility.

Embedded within Wolgos childhood and upbringing is an emphasis on physical prowess and athleticism. Early involvement in sports plays a significant role in their development, offering a subtle yet essential facet of their upbringing. Sports serve as a channel for the innate competitiveness of Wolgos children. By engaging in sports and physical activities, they direct their intense energy into controlled and structured environments. This outlet not only fosters healthy competition but also instils essential life skills such as discipline, teamwork, and respect for rules. Sports serve as a microcosm of Wolgos society, where adherence to rules and regulations is paramount. Wolgos children learn to respect boundaries, understand the importance of fair play, and manage both victory and defeat.

Formal education for Wolgos children typically commences around the age of ten. Yet, their early years are crucial in shaping their unique psyche. A well-rounded Wolgos upbringing aims to produce industrious, resourceful, and loyal individuals who excel in navigating intricate social dynamics and possess a strong sense of independence. Its important to note that if Wolgos children are raised in environments resembling those of humans, they may develop maladaptive traits, including severe anger issues, destructive tendencies, unnecessary malice, stubbornness, and a propensity for violence.

The Wolgos have not historically been known for their close bonds with animals, and in ancient times, they faced challenges in making the technological leap to animal domestication. However, over time, they learned from humans how to keep animals and have since adopted the practice, albeit with their unique approach. Wolgos now keep pets, although these animals are valued more for their prestige and utility than purely for companionship.

Wolgos children receive early lessons in responsibility and the importance of treating animals with care. They are taught to recognize the usefulness of these animals and are made aware of their potential for fierceness. It's not uncommon for Wolgos boys to take pride in raising and caring for some of the more aggressive dog breeds that the Wolgos tend to prefer.

Surprisingly, despite the inherent risks and dangers, Wolgos society encourages children to care for such animals as a means of mitigating their inherent impulses towards cruelty and their hunting instincts, especially when it comes to interactions with animals.

Elderly Years

Wolgos societies exhibit a notable age disparity, particularly in their advanced years, with Wolgos women typically outliving their male counterparts by almost a decade. This gap in life expectancy can be attributed to the challenging and often violent lives led by Wolgos men, which can lead to earlier mortality.

As Wolgos women enter their elderly years, they assume a vital role in their communities. They are often celebrated and respected for their culinary and homemaking skills, with many taking on the role of educators for younger Wolgos women, passing down the traditions of housekeeping and community care.

In contrast, elderly Wolgos males, as they experience a decline in physical prowess and influence, tend to recede from the forefront of community life. They may choose to lead more solitary lives, relying on the support and care of their wives. While they continue to participate in family matters and offer guidance when sought, they often lead quieter existences.

Both elderly Wolgos men and women rely on their families and fellow elders for mutual support, even though they may have limited means. In cases where elderly individuals find themselves without family support, it is not uncommon for them to live in communal arrangements with other elderly members of their tribe. By pooling their meager resources, they increase their chances of survival.

Traditionally, in Dhownolgos and subsequent Wolgos societies, individuals who consider themselves too old to continue living or believe they have become burdens undertake a final pilgrimage to special shrine routes, a pilgrimage known as Mr̥tōdǵhem Deywōwelnos. These routes are typically located in remote wilderness areas and offer only the most basic forms of shelter, such as man-made caves, hollows, or stone rooms. It is during this journey that they ultimately succumb to hunger, exposure, or other natural causes. Before their passing, they are expected to contribute to the upkeep of these shelters, including the removal of any bones or remains from previous pilgrims, thereby embracing their final act of unity with their god and race.

Morality

In Wolgos societies, morality is not defined in the binary terms of right and wrong as it often is in human cultures. Instead, their ethical framework is deeply rooted in the concept of balance and equilibrium, shaping a unique perspective on actions and consequences. The Wolgos do not perceive actions through the lens of right or wrong but rather consider the impact of these actions on the balance of their personal well-being, their immediate social circle, and the wider community. This approach is fundamentally different from human morality, which often hinges on universal principles of ethics. For the Wolgos, the primary consideration is how an action contributes to or detracts from a state of equilibrium, both within themselves and in their external relationships.

Maintaining social harmony is paramount, and individual actions are assessed based on their contribution to this harmony. Actions that might be deemed aggressive or even violent in human terms can be acceptable in Wolgos society if they serve to uphold social order, assert necessary dominance, or protect their community. Interpersonal conflicts and displays of strength are natural components of maintaining their societal structure, and such actions are not judged in moral terms but are seen as integral to their societal functioning.

The Wolgos' interactions with other species are guided by this same principle. They may engage in behaviour that humans perceive as unethical, such as manipulation or indifference to human life. However, in the Wolgos' view, these actions might be justified if they align with their goals or help maintain the desired balance of power. Their ethical system is context-dependent, allowing for a flexible and adaptive approach to inter-species relations. Actions that humans might consider immoral could be perfectly acceptable or even commendable within Wolgos society.

Implications for Human-Wolgos Relations

The Wolgos, having evolved as predators with humans as one of their ancient prey, carry within them an innate antagonism towards humans. This instinctual predisposition in the Wolgos manifests in ways both subtle and profound, often unconsciously shaping their behaviour and attitudes. Driven by subtle primal instinct echoes, the Wolgos might display an inherent sense of superiority and exhibit unconscious aggressive tendencies in their dealings with humans.

The moral framework of the Wolgos stands in stark contrast to that of humans. Centred around the concept of balance and equilibrium rather than the human dichotomy of right and wrong, the Wolgos assess actions based on their impact on personal well-being and community harmony. This perspective often leads to actions that might be viewed as aggressive, manipulative, or unethical by human standards but are seen as necessary and morally justified within the Wolgos society to maintain societal balance.

The divergence in moral perspectives can lead to significant misunderstandings and conflicts in human-Wolgos interactions. The Wolgos, guided by their moral viewpoint that prioritizes societal equilibrium, might engage in behaviours that are antithetical to human ethical principles. For instance, their predatory instinct, combined with a moral framework that does not align with human notions of right and wrong, can result in actions that humans find morally reprehensible.

For a peaceful coexistence, there is a crucial need to acknowledge the instinctual biases rooted in the evolutionary history of the Wolgos and the differing moral compasses of both species. Humans must understand that the actions of the Wolgos are influenced by deep-rooted evolutionary instincts and a moral framework that significantly differs from their own. Conversely, the Wolgos, in their efforts to coexist peacefully, must navigate the human moral dichotomy of right and wrong, which may seem alien to their understanding of balance and equilibrium.

Bridging these divides requires careful negotiation, deep respect for inherent differences, and an appreciation of the instinctual and moral factors that drive each species' behaviour. Building trust and mutual understanding involves diplomatic efforts and a recognition of the complexities that define the relationship between humans and the Wolgos.

Wolgos Archaeological Neolithic Reconstruction

The Wolgos were a formidable and deadly hominid subspecies, their unique anatomical and psychological differences shaped by and shaping their survival strategies in the Neolithic era. These adaptations, reconstructed from archaeological evidence, Wolgos cave paintings, and linguistic and folkloric remnants, highlight their evolution into efficient and strategic predators. Their physical prowess, strategic intelligence, and psychological manipulation all played crucial roles in their ability to dominate their environment and prey on early human tribes.

Evolutionary Adaptations and Survival Strategies

The Wolgos exhibit significant sexual dimorphism, with males standing around 7 feet tall and possessing a muscular build that far surpasses that of humans. This size and strength made them formidable in direct confrontations, capable of overpowering their prey with sheer force. Females, while closer in size to humans, were equally adapted to their roles in the Wolgos' predatory strategies. Both genders benefited from adaptations that enhanced their peripheral vision and situational awareness, compensating for the involuntary eye movements (nystagmus) caused by their albinism. Despite their photosensitivity, the Wolgos thrived in low-light conditions, leveraging their superior night vision to excel in nocturnal and crepuscular activities.

These physical attributes and the challenges they presented led to the development of specific survival strategies. The Wolgos' visual deficiencies, particularly tens of thousands of years ago when their eyesight issues were at their worst, necessitated a preference for ambush, stalk, and lure tactics rather than outright chases. Their photosensitivity made hunting during bright daylight hours particularly difficult and risky. As a result, they avoided hunting at noon or in open areas with intense sunlight, preferring the cover of forests or twilight periods when their vision and stealth were most effective. This limitation was a significant disadvantage, as it confined their activities to specific times and environments, reducing their hunting opportunities.

This need to rely on stealth and strategic positioning shaped their physical evolution, leading to increased size and strength to ensure overwhelming power when they did strike. Their higher caloric needs, estimated to be around 5000 calories per day compared to the 2000 calories required by humans, further drove their specialization in these hunting methods. They could not afford the energy expenditure of long chases and instead focused on energy-efficient stalking and ambushing techniques. This caloric demand also reinforced their predatory efficiency, as they had to ensure successful hunts to meet their substantial energy requirements.

The Wolgos' visual deficiencies and increased caloric needs created a positive feedback loop in their evolution. Their need for stealth and ambush tactics drove the development of their physical attributes—greater size, strength, and stable night vision. These traits, in turn, reinforced their reliance on these hunting methods, further specializing their predatory strategies. This continuous adaptation ensured the Wolgos' dominance in their environment and their role as apex predators.

Their evolution into such formidable predators also had profound social and cultural implications. The distinct roles of males and females in their predatory strategies influenced their social structures and behaviours. Males, tasked with direct confrontations and protection, developed highly protective and possessive behaviours toward their female partners. This protectiveness ensured the safety of the females, who played crucial roles in setting traps and lures. Strong social cohesion within the Wolgos group was essential for coordinated and effective hunting strategies, reinforcing their tightly knit social structure.

The Wolgos' cultural practices and rituals also reflected their predatory nature. Training in hunting and ambush tactics was a fundamental aspect of their upbringing, with cultural rituals emphasizing the importance of these strategies. These practices ensured that each generation of Wolgos was adept at maintaining their survival.

Territorial Management

The Wolgos demonstrated strategic intelligence through their mastery of their environment and covert living strategies. They controlled vast territories, maintaining them in a state that appeared untouched and fertile to attract human settlers. This extensive land management included manipulating local wildlife and resources to create zones of attraction and danger. By encouraging bees to nest in strategic locations, enhancing natural fishing spots, and placing human artefacts to pique curiosity, the Wolgos lured humans into precarious situations. Despite their careful planning, these strategies were not fool proof and required constant adaptation to changing conditions and human behaviours.

Their strategic intelligence extended to diverse lure tactics. Honey traps involving human-sized female Wolgos were frequent as a strategy, but they employed a wide range of methods to attract prey. These included using natural features like abundant fishing spots and bee colonies, as well as strategically placed human relics to draw humans into dangerous areas. By encouraging humans to adopt risky living strategies and disperse into small groups, the Wolgos increased their chances of capturing and manipulating their prey. However, these tactics also carried risks, as the humans' increasing wariness sometimes led to unexpected confrontations and losses for the Wolgos.

Psychological and Biological Warfare

The Wolgos excelled in psychological and biological manipulation, using their unique oral microbiome to produce scopolamine-like substances. These substances, introduced through licking, spitting, or kissing, made humans pliable and suggestible. Captured humans were subjected to conversation and psychological manipulation, turning them into unwitting agents who led other tribe members into traps. This gradual reduction of human numbers created an atmosphere of fear and mistrust, weakening social cohesion and making tribes more vulnerable. However, the effectiveness of this manipulation varied, with some humans developing resistance or escaping to warn others.

Their tactics were varied and sophisticated. One frequent method, evidenced in archaeological and folklore records, was the honey trap, where female Wolgos, appearing as vulnerable and alluring, would lure lone human males into secluded areas. These females often feigned friendship or distress, using their sexual allure to make their stories more plausible yet untraceable, ensuring that other humans would not believe in the Wolgos' existence. Another tactic involved creating scenarios that seemed harmless or beneficial to humans, such as leaving useful tools or food in areas they wanted to trap.

Additionally, the Wolgos would occasionally engage in seemingly benign interactions with humans, offering help or companionship to gain their trust. These interactions were meticulously planned to isolate individuals, making them more susceptible to the Wolgos' biological and psychological manipulation. By presenting themselves as misunderstood or benign, the Wolgos could effectively deceive humans into letting down their guard.

The Wolgos' use of psychological manipulation was complemented by their strategic predation. Initially, they subtly reduced human populations through small-scale captures and ambushes, making it difficult for humans to detect a pattern. As humans began to suspect the danger, the Wolgos shifted to more aggressive tactics, launching coordinated attacks to exterminate the remaining population. They meticulously removed all traces of human habitation, returning the land to a state of apparent virgin wilderness, ready to lure the next group of settlers. This strategy, while effective, required significant resources and cooperation among Wolgos, sometimes leading to internal conflicts and challenges in maintaining their territory.

Cultural and Social Structure

The Wolgos' cultural and social structures were deeply intertwined with their predatory strategies. There was a clear division of labour, with males focusing on physical dominance and protection, while females specialized in strategic deception and manipulation. This division was not merely a practical adaptation but a cultural norm, reinforced through generations. Both genders underwent rigorous training in their respective roles, with cultural rituals and rites of passage emphasizing their tactics and strategies.

Males, due to their larger size and greater strength, were the primary enforcers and protectors of the group. They honed their skills in combat and ambush tactics, ensuring they could overpower any threat. Their training began in early childhood, focusing on building physical strength, endurance, and combat skills. This rigorous training ensured that by adulthood, Wolgos males were formidable warriors capable of defending their territory and overpowering human prey.

Females, on the other hand, were trained in the art of deception and psychological manipulation. From a young age, they learned how to use their appearance and wiles to lure and trap humans. This training included acting, persuasion, and the subtle use of body language to create a façade of vulnerability or allure. Cultural rituals often celebrated the success of these deceptive tactics, reinforcing their importance within Wolgos society.

The protective and possessive behaviour of Wolgos males towards their female partners was a crucial aspect of their social structure. This protectiveness was not merely a result of emotional attachment but a strategic necessity. Females were key players in their hunting strategies, and their safety was paramount to the group's success. This dynamic fostered strong social cohesion within the Wolgos group, as each member's role was vital to their survival.

Despite their predatory nature, the Wolgos maintained a tightly knit social structure that supported their survival and success. The bonds within the group were strengthened through shared experiences, mutual dependence, and cultural practices. Group cohesion was reinforced by rituals that celebrated successful hunts and honoured the roles each member played. This tight social fabric allowed the Wolgos to operate efficiently and effectively, ensuring their dominance in their environment.

Reconstructed Evidence and Folkloric Remnants

Archaeological evidence, such as Wolgos cave paintings, provides valuable insights into their predatory strategies and social structures. These paintings depict scenes of hunting, luring, and ambushing human prey, emphasizing the importance of strategic planning and coordination. The detailed nature of these paintings suggests that the Wolgos placed great importance on recording their hunting techniques and successes, possibly for instructional or ritualistic purposes.

Linguistic remnants and folklore from human and Wolgos interactions also shed light on their methods. In northern Anaria, legends of pale forest succubi still persist, likely originating from the Wolgos' honey trap tactics and their psychological manipulation of human tribes. These legends describe elusive, ghostly figures that lure unsuspecting individuals into the forest, never to be seen again. Such stories reflect the deep-rooted fear and fascination that humans had towards the Wolgos, influenced by their predatory behaviors.

Additionally, remnants of Wolgos language and terminology found in ancient texts and inscriptions highlight their focus on stealth, strategy, and dominance. Words related to hunting, deception, and power frequently appear, indicating their cultural priorities. These linguistic traces offer a glimpse into the mindset and values of the Wolgos, reinforcing their image as cunning and formidable predators.

Folkloric remnants also reveal how human societies perceived and responded to the Wolgos. Tales of mysterious disappearances, strange encounters, and warnings about venturing into certain areas are common in the oral traditions of northern Anaria. These stories served as cautionary tales, warning of the dangers posed by the Wolgos and their sophisticated tactics. The persistence of these legends underscores the lasting impact of Wolgos predation on human culture and collective memory.

Neolithic Decline of the Wolgos

Archaeologists and anthropologists have long been fascinated by the dramatic decline of the Wolgos, a once-dominant hominid subspecies that roamed expansive hunting grounds across Stoldavia and Thultania in northern Anaria. Recent studies suggest that the domestication of dogs by human tribes played a crucial role in catalysing this decline. Evidence points to the critical impact of dogs on the Wolgos' ability to hunt, their social structures, and ultimately their population numbers.

Analysis of ancient human and Wolgos settlements reveals that the introduction of domesticated dogs significantly altered the dynamics of human-Wolgos interactions. Early signs of conflict, such as increased fortifications in human villages and the sudden appearance of dog remains alongside human artefacts, suggest a defensive response to Wolgos predation. Dogs, with their superior senses of smell and hearing, provided early warnings of approaching Wolgos, allowing humans to better prepare and defend themselves. This marked a turning point in the balance of power between humans and Wolgos.

The presence of dogs forced the Wolgos to adapt their hunting strategies, often with limited success. Evidence from Wolgos hunting grounds indicates a shift from ambush tactics to more desperate and risky behaviours. The need to avoid detection by dogs meant that Wolgos had to expend more energy and take greater risks during hunts. This increased energy expenditure, coupled with their higher caloric needs, placed immense strain on their populations. Hunting success rates declined, leading to food shortages and internal strife within Wolgos communities.

A decline in population numbers is evident in the archaeological record, with fewer Wolgos remains found in later layers of excavation sites. The combination of increased risks from hunting and genetic vulnerabilities accelerated their decline, leading to a near-extinction event. Additionally, the shrinking population led to a significant reduction in technological innovation among the Wolgos. With fewer individuals to share knowledge and drive progress, their ability to develop new tools and strategies was severely hampered.

By the time the Wolgos population had shrunk to approximately 400 individuals, the landscape of Stoldavia and Thultania had changed irrevocably. The surviving Wolgos were forced to adapt to a new way of life, relying less on direct predation of humans and more on alternative food sources and social strategies. Some evidence suggests that these Wolgos may have integrated into human societies in limited ways, possibly as mercenaries or in other specialized roles.

Notes

| Wolgos Sub-species | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Physiology topics: Wolgos Psyche - Wolgos Development From Birth to Adulthood - Death for the Wolgos - Wolgos Sexuality - Wolgos Masculinity - Wolgos Womanhood | |||||

| Historic and current Nations of the Wolgos | |||||

| Dhonowlgos | The Bind | Hergom ep swekorwos | United New Kingdoms | ||

|

|

||||

| ~3000 CE - 7505 CE | 7508 CE - 7603 CE | 7608 CE - Present | |||

| History & Geography |

History of Dhonowlgos: History of Dhonowlgos - Stained Era - Era of Rising Lilies

|

|---|---|

| Politics & Economy |

Dhonowlgos Politics: Politics - Foreign Relations

|

| Society & Culture |

Dhonowlgos Society: Monuments - Society - Brochs of Dhonowlgos

|

| History & Geography |

History of The Bind: History - Geography - Military - Science - Brochs of The Bind

|

|---|---|

| Politics & Economy |

Politics of The Bind: Politics - Military - Administrative Divisions of the Bind

|

| Society & Culture |

Society in The Bind: Brochs of The Bind - communication in The Bind - Demographics

|

| History & Geography |

History of The United New Kingdoms: History

|

|---|---|

| Politics & Economy |

Politics of The United New Kingdoms: Politics - Military

|

| Society & Culture |

Society and Culture in The United New Kingdoms: Wolgos Culture in the UNK - Demographics - Humans of the UNK

|