History of Hergom: Difference between revisions

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

The remnant government of the Bind sought to remain as the government of the Wolgos and orchestrated much of the exile logistics. Despite the hope of the Hlrike to preserve the Bind, they had lost most of their legitimacy as the rulers of Wolgos kind, and the Second Wolgos trek totally bankrupted the remaining administration of the Bind and their meagre remaining funds. The Wolgos zeitgeist post the scourge was of survival, and they identified the survival of the Bind as a possible lightning rod that would hinder their survival; as such, the public hindered all attempts of the Hlrike to resuscitate their legitimacy. | The remnant government of the Bind sought to remain as the government of the Wolgos and orchestrated much of the exile logistics. Despite the hope of the Hlrike to preserve the Bind, they had lost most of their legitimacy as the rulers of Wolgos kind, and the Second Wolgos trek totally bankrupted the remaining administration of the Bind and their meagre remaining funds. The Wolgos zeitgeist post the scourge was of survival, and they identified the survival of the Bind as a possible lightning rod that would hinder their survival; as such, the public hindered all attempts of the Hlrike to resuscitate their legitimacy. | ||

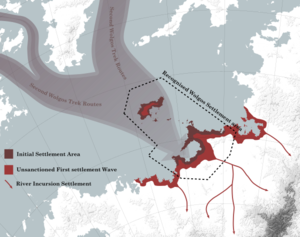

Kupeya at the time was considered a highly forested dark heart of Gotha, hidden behind the Shangti archipelago and jungles of Raia from what was considered Civilization. Everything south of the Sirchipur (now known as Lukonos) highlands was considered a largely unexplored land of dense old-growth forests that, after thousands of kilometres, led to never-ending boreal forests. No infrastructure existed, and the humans that lived in Kupeya were largely nomadic and consisted of small tribes hidden within the forests. Kupeya was never previously colonised by any power due to its remoteness, and only the Ithrieni had ventured into its rain and storm-battered hinterlands. | |||

The islands off the Kupeya coast, now known as the Hepwes Islands and the Peleykros peninsula were marked for Wolgos resettlement, the regions once considered the most hospitable and best-mapped regions of Kupeya. The Wolgos were not to venture beyond the demarcation lines, with the rest of Kupeya being negotiated as an international preserve. The "preserve of Kupeya" was never made into a recognised agreement and only existed as a nebulous concept held by the many powers that were unwilling to cause conflict over an extremely remote and believed to be hostile land. In fact, many cartographers believed that an unseen mountain range must lie not far from the first few hundred kilometres of the coast, with the rest being covered by the unexplored southern ice cap. | |||

== 7608 Foundation of Hergom ep Swekorwos == | == 7608 Foundation of Hergom ep Swekorwos == | ||

Revision as of 00:50, 4 October 2024

Pre-Wolgos History

For much of its historical narrative, Kupeya remained ensconced within a realm of limited development. Its northern coast extended as a slender belt of temperate land, while the continent itself boasted a penchant for climatic variability that rendered its colder boreal interior inhospitable to pre-industrial societies.

Along this coastal fringe, a string of modest Chalam princedoms emerged over time, forming clusters of villages dependent upon subsistence farming and fishing. These entities occasionally engaged in trade with the warmer Raian archipelago, a connection that punctuated their existence.

Venturing further into the continent's heart revealed hunter-gatherer villages strewn across the landscape, punctuated occasionally by subsistence trading communities settled along the meandering banks of the continent's intricate river networks. The Phula and Alutean peninsula, in contrast, gave rise to societies of greater advancement, characterized by their capacity to erect permanent stone and earth mound temples. Within most of these villages and towns, palisades stood sentinel, and communal grain silos stored the bounty of the subtropical climate, offering these societies an abundance of crops.

Among these regions, Alutea stands as the sole recipient of Ithrien's colonial influence. Trading outposts and coastal holdings established by Ithrienian lords endowed Alutea with a more advanced societal landscape. In exchange for valuable commodities such as cassava, sea products, and even slaves, Alutea engaged in an exchange with Ithrien, elevating its position on the developmental spectrum.

Kupeya occupies a place of profound historical remoteness within the fabric of Gotha, a distinction shared only with central Davai. Its proximity to the southern polar cap shielded Kupeya from the classical hemisphere and its confinement by the dense Raian archipelago to the north have sealed its isolation. This archipelago, once a sprawling realm cloaked in rainforest and coastal cultures trading in spices and tropical treasures, bore witness to piracy and commerce.

Despite its geographic connection to Raia, the region bordering Kupeya has remained veiled in dense, nearly impenetrable rainforests. Consequently, the allure of colonization never extended its grasp here, untouched by the ambitions of both Anarians and Western Davai. Anarians mapped and explored the region but ultimately viewed it as less promising compared to the fertile colonial prospects of Altaia, D’runia, Tzeraka, and the Shangti.

7603 - 7620 - Second Wolgos Trek

As a direct result of the Wolgos scourge, Kupeya was transformed from the most isolated and least explored region in Gotha to the modern powerhouse of today. The Wolgos Scourge led to the Second Wolgos Trek, where over 12 million Wolgos were transported from the old territories of the Bind to Kupeya using two thousand ships that travelled non-stop over ten years, With the majority being transported over the first five years. Of the estimated fifty million Wolgos in the Bind, only around thirteen million survived, with the vast majority being transported to Kupeya while the remaining million largely coalesced into the United New Kingdoms and the rest became scattered across the Shangti ocean islands.

The two thousand ships were largely large cargo ships and ocean liners of various kinds modified to allow the mass transport of Wolgos and the required goods to settle in Kupeya. Most came from the Bind itself and its merchant marine, while others were given to the Wolgos as part of the peace agreement post-Wolgos Scourge. These ships burned coal and transported around fifteen hundred Wolgos at a time with an average turnaround time of thirty days as they transversed the eleven thousand kilometres of ocean to Kupeya.

Along with the wolgos, over two hundred thousand Shriaav that benefited from the Wolgos rule of the Bind came along with the Wolgos. These sharia would have likely perished as their brethren sought retribution for their collaboration with the Wolgos. Some wealthy shriaav procured their own vessels and joined the convoys of the Second Wolgos trek. These shriaav have the distinction of having cooperated with the Wolgos to transport just over a million Eokoesr and Eraci (Eokoesr/Ak'lam mix), an operation that brought them many continued benefits in Kupeya and infamy post-second Trek outside Hergom. Nevertheless, it is recognised that the war-tired powers paid no heed to the rumours of such transports.

The fleet transported not only the Hominids but also as much art, artefacts, machinery, building material, and technology as the Wolgos would require to survive in Kupeya. The peace agreement between the Wolgos people and the powers of Gotha, the Perkgos agreement, forbade them from taking machinery that could be used to manufacture war equipment or take existing war equipment. Nevertheless, the Wolgos, from the very beginning of the Second Trek, broke the agreement and prioritised the covert transport of weapons and ammunition stockpiles along with the disassembled war boundaries of New Xedun to Kupeya.

The remnant government of the Bind sought to remain as the government of the Wolgos and orchestrated much of the exile logistics. Despite the hope of the Hlrike to preserve the Bind, they had lost most of their legitimacy as the rulers of Wolgos kind, and the Second Wolgos trek totally bankrupted the remaining administration of the Bind and their meagre remaining funds. The Wolgos zeitgeist post the scourge was of survival, and they identified the survival of the Bind as a possible lightning rod that would hinder their survival; as such, the public hindered all attempts of the Hlrike to resuscitate their legitimacy.

Kupeya at the time was considered a highly forested dark heart of Gotha, hidden behind the Shangti archipelago and jungles of Raia from what was considered Civilization. Everything south of the Sirchipur (now known as Lukonos) highlands was considered a largely unexplored land of dense old-growth forests that, after thousands of kilometres, led to never-ending boreal forests. No infrastructure existed, and the humans that lived in Kupeya were largely nomadic and consisted of small tribes hidden within the forests. Kupeya was never previously colonised by any power due to its remoteness, and only the Ithrieni had ventured into its rain and storm-battered hinterlands.

The islands off the Kupeya coast, now known as the Hepwes Islands and the Peleykros peninsula were marked for Wolgos resettlement, the regions once considered the most hospitable and best-mapped regions of Kupeya. The Wolgos were not to venture beyond the demarcation lines, with the rest of Kupeya being negotiated as an international preserve. The "preserve of Kupeya" was never made into a recognised agreement and only existed as a nebulous concept held by the many powers that were unwilling to cause conflict over an extremely remote and believed to be hostile land. In fact, many cartographers believed that an unseen mountain range must lie not far from the first few hundred kilometres of the coast, with the rest being covered by the unexplored southern ice cap.

7608 Foundation of Hergom ep Swekorwos

7632 - 7634 First Coalition War

Phase one

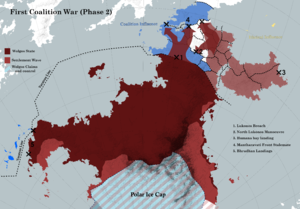

After three decades marked by reconstruction and ambitious natality policies, both Hergom and the Wolgos had expanded far beyond the original containment zone established following the devastating Wolgos Scourge. Almost yearly, since Hergom's inception, the containment zone had been pushed further through a series of somewhat half-hearted treaty amendments. These amendments were often in response to "rogue" Wolgos settlers venturing beyond the vast and poorly patrolled borders. However, this expansion strategy had its limits, and the nations of Livaria, Kamura, and Ithrien soon grew weary of this unchecked expansion. In response, they established a genuine boundary, jointly patrolled by all three nations, in a concerted effort to halt Wolgos expansion.

For a decade, the Wolgos were effectively contained. Yet, as the world's powers redirected their focus elsewhere, the Wolgos seized the opportunity to amass their strength and meticulously plan their next move. This culminated in the outbreak of the First Coalition War in the spring of 7632. At the time, the Wolgos were still in the process of redeveloping their military industry, and their strength lay more in their sheer numbers than in the sophistication of their equipment. The conflict was predominantly waged with infantry, cavalry, and lightly armored vehicles based on Wolgos civilian truck and automobile designs.

The war erupted on multiple northern fronts, with the breach of the Pelaghr border against the Ithrieni defensive line being particularly swift. The small Ithrieni garrisons, along with poorly equipped Chalam vassals, were quickly overwhelmed, allowing the Wolgos to advance northward. Skirmishes with fragmented Chalam states followed, but their lack of organization made them vulnerable prey for the Wolgos.

In the rugged Lukonos highlands, the Livarian and Kamuran garrisons presented a much more formidable defense, one that remained unbroken during the initial phase of the war. In fact, during this phase, the Livarians and Kamurans even managed to launch the Vatama counteroffensive, which penetrated deep into Hergom's territory before ultimately being pushed back.

The war was characterized by swift-moving, light troops, with the goal of occupying as much territory as possible before reinforcements from the dominant powers of the era could arrive. Ithrien, being the nearest to the conflict, managed to bring reinforcements within five months and established a fortified fallback line at the Lanan Isthmus. Fortunately for Hergom, Ithrien was grappling with second-rate power status, lagging behind most nations in terms of military prowess and defense capabilities. The Ithrieni soldiers fought valiantly for weeks, but over time, the Wolgos breached the Lanan Isthmus line, occupying Alutea and driving the Ithrieni forces off the mainland.

Phase Two

During the second phase of the conflict, the Wolgos focused on consolidating their occupation of the Ithrieni zone of influence. They successfully repelled Ithrieni attempts, such as landings at places like Humana Bay. With firm control established over the Ithrieni region, the Livarian and Kamuran zones of influence became significantly more vulnerable. Attacks on their rear positions became increasingly frequent.

In a matter of weeks, the Lukonos line, once deemed impregnable, was breached, forcing the coalition forces to retreat northward. Although Livarian and Kamuran reinforcements were dispatched, the vast distances involved led to a delay in their arrival. However, when these reinforcements finally reached the front lines, they, along with the retreating forces, managed to establish the formidable Mantharavati line.

The Mantharavati line, characterized by its resilience, remained unbroken throughout the war. It became a theater of intense conflict, with both sides engaging in frequent attacks and counterattacks for over six months. Despite the ferocity of these clashes, little progress was made.

As the war dragged on, a certain weariness settled in, and a stalemate was reached at the Mantharavati line. The coalition, recognizing the enormous resources and manpower required to continue the grand war with the Wolgos, became increasingly unwilling to invest in the conflict. Negotiations, brief and influenced by a sense of apathy from the major powers involved, followed.

Ultimately, the lines of conflict became the new international borders, marking a somewhat awkward peace. The war had taken its toll, and the Mantharavati line, which had borne witness to so much bloodshed, now stood as a demarcation between the warring factions, ushering in an uneasy era of post-war tranquility.

7634 - 7663 Interwar Period

In the aftermath of the tumultuous first coalition, Hergom entered an enigmatic era marked by introspection and silence. While the nation appeared to withdraw from international affairs, beneath this veneer of seclusion, Hergom clandestinely maintained observation cells beyond its borders. Diplomatic overtures were left unanswered, and Hergom remained an enigma for twenty-nine years. Its coastlines, bristling with hostility, deterred any would-be incursions, while the boundary in the Varatran Line became a foreboding line of no return.

During this interwar period, Hergom's interaction with the outside world was largely circumstantial. Instances arose where foreign fishing vessels lost their way or cargo ships found themselves at the mercy of capricious weather, inadvertently straying into Hergom's waters. Tragically, all who ventured too close met swift and brutal destruction. Hergom exhibited a cold indifference, offering no assistance, leading to speculation that they might have exploited these hapless vessels for loot or forced labour.

Hergom's foreign policy during this time was characterized by a steadfast refusal to actively engage with the outside world, except in cases of conflict or territorial expansion. The nation remained resolute in its commitment to strengthen its industrial base and military might, with a vision of cyclically embarking on expansionist campaigns. It is now known that Hergom anticipated the possibility of large-scale offensives roughly once every decade. Wolgos State devised ambitious plans to extend its dominion, with aspirations of encompassing the entirety of Tzeraka and Raia, stretching as far as the Jaladhara River within the next three decades.

Hergom's audacious endeavors to colonize the inhospitable southern polar cap came at great expense. The islands of the Meghes Hweytos in the Antarctic Sea became host to a network of military outposts, initially established for surveying the snow-free mountains and the concealed riches beneath their icy veneer. Over time, these outposts evolved into fishing stations and diamond mining ventures, providing essential resources for their sustenance. The more prosperous outposts burgeoned into small towns, supporting forward military bases. Meanwhile, the southern face of the Hrheghgelon Mountains bore witness to a grim chapter in Hergom's history. Forced labor camps proliferated, extracting nickel and platinum from the unforgiving landscape. Hundreds of thousands of Utura and Chalam laborers perished while toiling to construct the now-infamous Blistered Souls railway, serving the numerous mines in the region.

In Alutea and northern Kupeya, Hergom executed a swift and ruthless campaign of pacification and integration. The populous Gahnam of Alutea, Phula, and Hastos were systematically reorganized into Wolgos-style tribes, and their lands were transformed into nominally autonomous territories. Wolgos settlers arrived in force, and the Gahnam elite were coerced into fragmenting their population into easily controlled and isolated provinces. Razor wire fences sprang up between these provinces, and movement between them was tightly regulated. As Wolgos industry and agricultural enterprises took root, the Gahnam elite were compelled to provide labor for burgeoning agricultural projects. Gradually, these regions transformed into one of Hergom's leading breadbaskets, bearing the indelible marks of their turbulent integration.

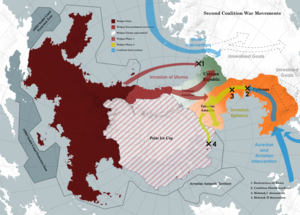

7663 - 7664 Second Coalition War

7664 - First use of nuclear weapons in Ephesus Front by the Coalition